While in pre-production for his space epic AD ASTRA, director James Gray turned to experimental film scholars Leo Goldsmith and Gregory Zinman to suggest experimental films to view about space, landscape, loneliness, and more, that could inspire the visual language for his film. On Saturday, October 12, at the Museum of the Moving Image, Goldsmith and Zinman will present a selection of the 50 films that they shared with Gray. Science & Film sat down with Goldsmith to discuss the collaborative process of selecting and sharing films on October 3.

Science & Film: How did you go about selecting films to show James Gray?

Leo Goldsmith: He was pretty open with what he was looking for. He had gone to MoMI [Museum of the Moving Image] to see the exhibition “To The Moon And Beyond,” for which Greg and I did the program in the amphitheater, screening a series of computer films from the 1960s, including works by John and James Whitney, Stan Vanderbeek and Kenneth Knowlton, and Charles Csuri. James was thinking about how Kubrick had been watching experimental films of that era, or at least was in dialogue with them, and that’s why he connected with us.

He was talking to people at NASA and at Elon Musk’s company, so the natural next step was of course to come to us. [laughs]

S&F: Was he only interested in space imagery?

LG: The remit was much broader. He was definitely thinking about space but he was also interested in new visual ideas, different ways of seeing and visualizing those spaces. We did send him things that were space-related, that was the place we started, sending him things like Scott Bartlett’s MOON 1969 and Jeanne Liotta’s ECLIPSE. But then as we went on we got looser with what we were sending him, from abstract digital works like Sabrina Ratté’s LITTORAL ZONES to more analog pieces like Jodie Mack’s LET YOUR LIGHT SHINE. As the correspondence went on, he did have some specific things that he was interested in. For example, at a certain point he asked about films about isolation and loneliness. The entire film almost takes place in the character’s head, and this idea of people being alone in the cosmos is a big theme.

S & F: What did you show him for those prompts?

LG: We showed him a couple of films by Ben Rivers. The obvious one was his feature film TWO YEARS AT SEA about a man who lives in the Scottish Highlands by himself; it’s a very poetic and beautiful film that has this romantic relationship of man in nature but is more complex than that and plays with that a little bit. The other film by Ben Rivers was a series called SLOW ACTION which is more about climate change. Even something like James Benning’s THIRTEEN LAKES, which is not a film about space – it is a film about physical space but it has a certain sense of depopulated landscapes and a complex relationship to romanticism.

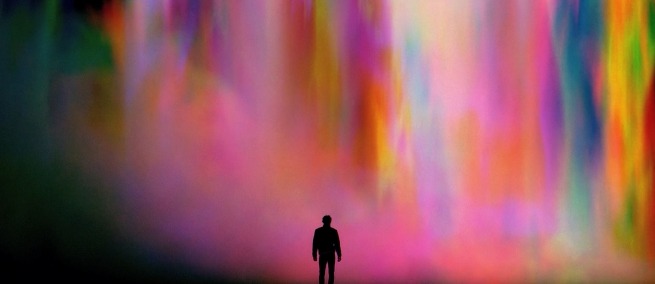

James Gray had shared a script with us so we sort of knew what the film was going to be and we could think about things that would be useful to him even if they weren’t necessarily like full-on about space. There is also a video by the Galician filmmaker Lois Patiño called STRATA OF THE IMAGE, which again has an iconography of the romantic human and nature relationship, but in this sort of psychedelic way—colorful, wonderful, which struck me as very sort of space-like.

He also had a couple of specific asks about certain kinds of physical phenomena that are not visible — gamma rays, specifically and how to visualize them. We sent a film called ENERGIE by Thorsten Fleisch which we’ll be showing at MoMI. We sent him some flicker films, some Paul Sharits, and a film by Jennifer West called SALT CRYSTALS SPIRAL JETTY DEAD SEA FIVE YEAR FILM, which, as the title suggests, records the effects of salt water on a piece of 70mm film floated in the Dead Sea for five years. These films that have a unique way of visualizing something sort of abstract, ephemeral, and could maybe have given him some ideas about how to create something that looks unique and unlike every space movie you’ve ever seen.

James was very conscious of the idea of he was working in a different mode from a lot of the people that we were showing him. He was working with a large budget, multiple people, and we were showing him works by, in most cases, individual filmmakers. He was very conscious of the big gap between what he was doing and what they were doing in terms of aesthetic practice and approach but also in terms of their economics and politics.

S&F: When you saw the film, was there anything that struck you as having been inspired by what you showed him? There were so many people working on this, of course.

LG: I know because I stayed till the end of the credits to see my name. [laughs]

I can see certain connections. There are certain moments of vistas and planets and space-scapes that have some relationship with things that we were showing him. But also in more abstract ways, like the pacing and the sound. One of the films that we showed him was STELLAR, a Stan Brakhage film from 1993. STELLAR is a film about the cosmos. It is silent, as many of Brakhage’s films are, but in relation to representations of space, that abstraction and lack of sound become more representational than many of Brakhage’s other works.

S&F: Were there any films that you know he really enjoyed?

LG: We showed him the music video for Let’s Groove by Earth, Wind & Fire, which is directed by a really interesting filmmaker/animator by the name of Ron Hayes. He was somebody who is not very well-known, who died of AIDS in the early 90’s, but he worked with a computer graphics system called Scanimate, which had been used on lots of logos for TV and it was used in some music videos as well. It has a very distinctive visual aesthetic of blurred light and vibrant color. James said his son really loved it. The way that it treats light and color is very distinctive and even though it may not be a direct influence, perhaps there’s a kinship there.

S&F: What was interesting to you about this project?

LG: Greg and I teach and write about experimental film, and we often think and talk about how these works function in relation to, say, mainstream commercial feature films. There are lots of connections and contrasts that interest us. The programs we were doing on computer films at MoMI, those films were made by individuals, but because of the nature of what they were working with—computers in the 60’s/70’s—they had to have had this relationship with commercial companies but also with the military, with NASA, with IBM, and Bell Labs. One of the first films that we showed James was UFOs by Lillian Schwartz, which she made at Bell Labs in collaboration with Ken Knowlton. We also showed a bit of a film by Pat O’Neill called WATER & POWER. Pat O’Neill’s whole career is really fascinating; he’s a very masterful technician of the moving image, from celluloid to digital media. He has an enormously rich body of work of his own, but he also worked on the special effects for THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK.

Greg and I have thought about the history of special effects a lot and we are fascinated by that kind of push and pull between the individual artistry and the way that it gets kind of incorporated—in some cases smoothly, some cases roughly—into more commercial work. There might be purists who insist on the separation of these practices, but it seems to me the moving image always has these connections. In the histories of technology there is no purity. This complex relationship between artistry and technology is intrinsic to the medium, and part of what’s fascinating is to think about how these things might be in dialogue with each other. It’s just as interesting to me as how they might be in conflict with one another.

Leo Goldsmith is a writer, curator, and teacher. His writing has appeared in Artforum, art-agenda, Cinema Scope, and The Brooklyn Rail, where he was film editor from 2011 to 2018. He is Visiting Assistant Professor of Screen Studies at The New School. On October 12 at the Museum of the Moving Image, he and Gregory Zinman will present a selection of short films that they shared with James Gray. For more about the making of AD ASTRA, read our interview with Gray’s scientific advisor Robert Yowell.

cover image: still from Lois Patiño's STRATA OF THE IMAGE

TOPICS