On the occasion of the annual “Cephalopod Week”—originated by Science Friday—Popular Science produced a charming video centered on the nautilus, a species of cephalopod that has survived five mass extinctions and has been in the ocean for over 500 million years. The video features archival footage (from the EYE Filmmuseum in the Netherlands) by John Ernest “J.E.” Williamson, one of the first people to make a film about undersea life. Williamson invented the photosphere, a mechanism that allows a camera to be taken underwater. The photosphere was used commercially first, and perhaps most famously, in the 1916 film adaptation of Jules Verne’s novel 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea, set on the submarine named Nautilus.

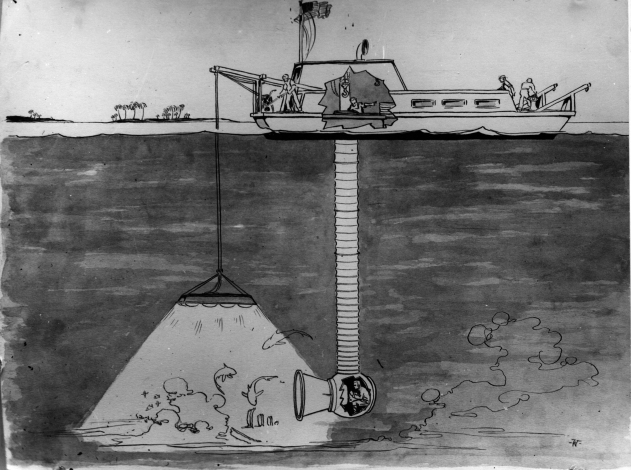

The photosphere is a spherical observation chamber in which a cameramen could descend beneath the sea. It is approximately five feet in diameter and an inch and a half thick, with a funnel-shaped glass window that offers a view into the ocean. The sphere is attached to the end of a deep-sea tube invented by J.E. Williamson’s father, a sea captain named Charles Williamson. The tube, composed of concentric, interlocking iron rings that allows it to stretch as an accordion does, could be attached to a ship and lowered to depths of up to 250 feet deep. Charles Williamson had originally designed this tube to assist underwater repairs. His son had other ideas. He repurposed the tube, attaching a photosphere at the bottom, with the idea of taking undersea photos and even motion pictures.

George Williamson, Carl Gregory (in the photosphere access tube), J.E. Williamson, 1914, Chapman University Film Collection

Williamson first experimented with the photosphere in 1912, proving that it could house a cameraman and provide a clear view of the deep. He took undersea photographs in 1912, in the waters of Hampton Roads, Virginia. Two years later, in 1914, Williamson took his device to the Bahamas, where sunlight shines up to 150 feet below the sea. The photosphere was attached to and dropped from a specially designed barge, the Jules Verne. William’s one-hour documentary THIRTY LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA featured a climax shot from the photosphere. A dead horse hangs upside down in the ocean. A man, played by Williamson himself, dives with a knife to stab an unsuspecting but seemingly menacing shark as it approaches the horse bait. THIRTY LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA was later renamed—more appropriately—THE TERRORS OF THE DEEP.

Drawing of the photosphere by J.E. Williamson, 1915, Chapman University Film Collection

Audiences responded to the film with amazement and lauded Williamson’s invention as a major achievement. An October 1914 review inThe Moving Picture World proclaimed that “Jules Verne is vindicated at last” and “the panorama is as entrancing as it is new.” The Evening Standard (23 July 1914) noted that the invention of the photosphere “has amazed the scientists and diplomats.” Other commentators looked forward to the future, when underwater films could be produced in color, and at even greater depths.

In 1916, Williamson’s undersea motion pictures captivated audiences worldwide with the release of Stuart Paton’s 20,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA. Not only did he shoot a nine-minute underwater sequence from the photosphere, but he took matters even more directly into his own hands to do justice to Verne’s fantastical descriptions of undersea life. Williamson was captivated by Verne’s giant squid, and wanted to show a 30-foot-long cephalopod: “the father of all octopuses,” as he later wrote in his autobiography.

Capturing such a large octopus was unsurprisingly challenging, so Williamson decided to buildthe giant octopus himself. Using the same ingenuity he’d applied to the invention of the photosphere, Wiliamson constructed a mechanical octopus that could move just as a real octopus would. Inside each tentacle were tapered springs that could extend and recoil. Sitting in a compartment not unlike the photosphere situated in the octopus’s head, a diver could direct pressurized air into these spring-loaded tentacles to make them squirm.

Battle with shark, 1914, Chapman University Film Collection

Williamson then had to enable the mechanical octopus to perform what he called “its most spectacular function--the throwing of a great cloud of ink,” (Williamson, Twenty Years Under the Sea, p. 70). After experimenting with gallons of writing-ink, which Williamson deemed too dark to realistically depict octopus ink, he came upon “a quantity of sticky marl from a swamp.” When the marl, an earthy mixture of varied sediment, was dropped into the sea it disipated, producing a sepia-toned “ink” that was satisfactorily comparable to octopus ink. In 20,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA, Williamson’s octopus squirmed and inked in strikingly realistic fashion.

J.E. Williamson's mechanical octopus (Twenty Years Under the Sea, p. 179)

Williamson was one of the first to invent a means of filming underwater, but was not alone. Scientific researchers such as William Beebe in the 1920s and ’30s brought cameras underwater to observe deepsea life for study. Other filmmakers, from Jean Painlevé (1902-89), to Jacques Cousteau (1910-97), to James Cameron (1954-), also invented their own means for documenting creatures of the deep. This cinema has contributed to understanding of and appreciation for marine ecosystems.

The Popular Science video, available to watch below, is also in that tradition. The beginning is shot in the laboratory of biologist Jennifer Basil at Brooklyn College. Tom McNamara, who directed the video, shows the nautilus at fantastic close up as it gulps air and undulates its tentacles. “You’re getting to peek into the world of an ancient brain,” Basil says in the video. Every week is “cephalopod week” for Dr. Basil; she studies the consciousness of nautilus.

J.E. Williamson would go on to shoot several films, including GIRL OF THE SEA (1920), WET GOLD (1921), WONDERS OF THE SEA (1922), and THE UNINVITED GUEST (1924), which was filmed in color.

For more on undersea filmmaking, listen to Jacques Cousteau’s grandson Fabien Cousteau talk with whale researcher Howard Rosenbaum about marine biology, conservation, and the legacies of William Beebe and Jacques Cousteau.

Cover image: View of a diver–possibly J.E. Williamson–from the photosphere, 1914, Chapman University Film Collection