On February 25, the Museum of the Moving Image’s Science on Screen series will present films taken between 1927 and ’34 by members of the Department of Tropical Research, which was a field research group led by famed ecologist and explorer William Beebe. Beebe is best known for his record-breaking deep-sea dives in a steel-walled submersible called the Bathysphere–3,028 feet down.

“Of the Deep: Films by The Department of Tropical Research” will feature live musical accompaniment by High Water. The program will be introduced by Vice President and Director of the New York Aquarium Jon Forrest Dohlin and followed by a discussion between marine mammal researcher Howard Rosenbaum (from the Wildlife Conservation Soceity) and Fabien Cousteau, grandson of explorer and filmmaker Jacques Cousteau and himself an aquanaut and filmmaker.

William Beebe, Bathysphere, Otis Barton (c) Wildlife Conservation Society

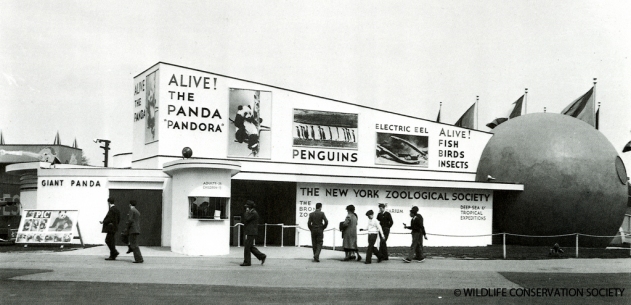

When William Beebe passed away in 1962, Department of Tropical Research (DTR) team member Jocelyn Crane became its director. The DTR was part of the New York Zoological Society, which today is known as the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), headquartered at the Bronx Zoo. The DTR was eventually folded into the WCS's Institute for Research in Animal Behavior, a forerunner of its current Global Conservation Program. Science & Film went to the Zoo to speak with Madeleine Thompson, archivist at the Wildlife Conservation Society Archives, about their collection of materials from the DTR and the other major collections they house. Thompson was co-curator–with artist Mark Dion and historian Katherine McLeod–of a 2017 exhibition featuring artworks made by members of the Department of Tropical Research.

Science & Film: What evidence is there of William Beebe’s passion for science communication in the Wildlife Conservation Society archives?

Madeleine Thompson: For me what is so appealing about Beebe is that focus on popular communication. Beebe certainly insisted that [the DTR’s] focus was on making important contributions to science, but in reality the impact [of what they were doing] was much more felt on the popular side of things: through their publications and lectures that Beebe and the DTR staff were giving.

Archival material in our collection related to this communication takes the form of drafts of his writings for popular audiences. We also have things like brochures advertising Gloria Hollister [a DTR member] as a lecturer. Then of course there are the illustrations, many of which appeared in popular publications, as well as materials related to the exhibition that [the New York Zoological Society] did at the 1939 World’s Fair.

S&F: What were the politics of gender within the DTR?

MT: Beebe certainly was encouraging of young women working in science. There is a quote we referenced in the catalogue [from the exhibition “Exploratory Works” at the Drawing Center] from the late 1920s. A woman, Jocelyn Crane, comes on board and another woman, Gloria Hollister, had already been involved in the DTR. Beebe says that he gravitated toward “adaptable scientific students who fall in with my plans, and sometimes women offer me just those qualities.” The first time I read that, I thought he was saying that women were more submissive. But reading it again, I wondered if he’s saying that he just has more in common with the way that women think. Regardless, he certainly was encouraging of women taking on leadership roles within the DTR. Gloria Hollister led her own DTR expedition to British Guiana in the 1920s. Jocelyn Crane became the assistant director of the DTR and Beebe’s chosen successor. There’s no question that he was supportive of women in science. Hollister and Crane are the two names that come up when we’re talking about this because they did the most sustained work of the time. But there were certainly a number of other women on all the expeditions, both scientists and the artists too. You’re talking about a time when it wasn’t unusual for women to be scientific illustrators, but what was unusual was for a woman to be going out in the field with a co-ed team.

DTR members (c) Wildlife Conservation Society

S&F: Also for a team to bring artists! How common was that?

MT: I don’t think that was entirely uncommon, but my impression was that the DTR had more artists than was typical. Also, within the DTR, the artist was a staff position and not some sort of auxiliary role. They were considered staff members of the New York Zoological Society and the DTR.

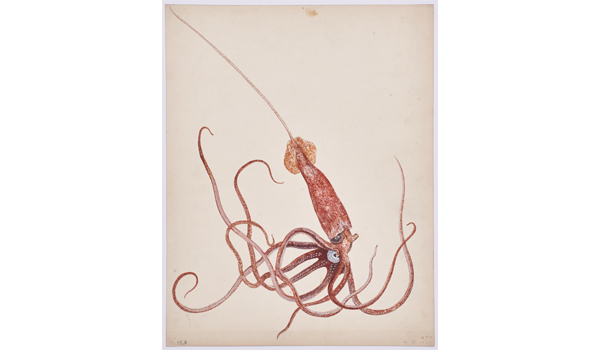

Their illustrations are so interesting. Seeing them at the Drawing Center, in a gallery, you see that they are gorgeous works of art. Seeing over 2,000 of them in the Archives, one after the other, you understand their function as field notes. At the same time, they were also forms of communication both for technical and popular audiences.

(c) Wildlife Conservation Society

S&F: Is there anything that you’ve read about why members would choose one artistic medium over another?

MT: My impression is that the photographs and films just couldn’t capture what they wanted at the time. They were certainly doing some experimentation with that and especially with the underwater photography and filming. With the drawings it’s really about capturing color that they couldn’t otherwise, and depicting narratives—of a predator/prey interaction, for instance.

S&F: Besides the Department of Tropical Research materials, what do people come to the Archive to research?

MT: One of our most consulted collections was created by William Hornaday who was the first director of the Bronx Zoo. He was a major figure in the wildlife conservation movement of the era and in developing that movement. He was also, thankfully for an archivist, a packrat and was certain of the importance of his work so he saved everything. Hornaday was involved in major decisions about the future of the Zoo and its development. He was brought on before the Zoo was even built so he was really influential in its construction. But then he was also involved in very little, everyday issues. He interacted with the public quite a bit—for instance, with members of the public who wanted to send the Zoo animals, even common animals like raccoons and box turtles.

Hornaday’s collection reflects his work as the Zoo’s director but also his heavy involvement in wildlife conservation actions. [Hornaday] was the driving force behind the foundation of the American Bison Society, an affiliate organization of WCS that started in 1905 and was re-launched by WCS in 2005. Hornaday, even before he came to the Zoo, was really interested in bison and the decimation of bison populations in the US. He worked with the American Bison Society to create preserves for bison out West and to populate them in some cases with animals from the Zoo. Hornaday also started a fund called the Permanent Wild Life Protection Fund that was the seed money for what ends up being WCS’s Global Conservation Program today.

William Beebe (c) Wildlife Conservation Society

S&F: At the Museum of the Moving Image we’re going to be showing some amazing films from the WCS Archives that were taken by members of the DTR. What can you tell me about the Archive's film collection?

MT: The film collection is something we’re really excited about. The WCS Archives was asked to assume management of the collection a few years ago. We are in the initial stages of inventorying and assessing the 3,000 reels in the collection, but we’re already aware of some really interesting footage–mostly dating from the mid-twentieth century—of the Bronx Zoo and the New York Aquarium, of international field work projects, along with some educational films made by the Society about conservation, and of course the DTR footage. We have a lot of work ahead of us as far as preserving this collection and making it accessible, but we’re thrilled about the value this collection can hold for researchers and others interested in this history.

The Wildlife Conservation Society’s mission is to save wildlife and wild places around the world through science, conservation, and education. Its Global Conservation Program protects endangered species in over 40 countries. The WCS Archives focus on material created by WCS staff and affiliates since its founding in 1895. It consists of about 1,200 linear feet of paper which includes correspondence and administrative records. There is a photography collection of about 54,000 negatives, and 3,000 reels of film. Eight hundred of those reels have been catalogued to date. “Of the Deep,” happening at the Museum of the Moving Image on February 25, presents reels of footage that WCS digitized in the past fifteen years featuring Beebe and DTR members on expeditions to Haiti and Bermuda.

Cover image: Gloria Hollister (c) Wildlife Conservation Society