In the upcoming Todd Haynes film WONDERSTRUCK, a wolf diorama from the American Museum of Natural History which is central to the narrative was, in reality, made by Carl Akeley. Akeley was the first cinematographer to film gorillas in the wild. In 1921, in present-day Zaire, he filmed MEANDERING IN AFRICA with a camera that he invented. Akeley was on an expedition for the American Museum of Natural History, where he was a curator and taxidermist; he used film mostly as reference material to create dioramas of the natural habitats of animals for the museum. One of the highlights of the Museum of the Moving Image’s collection is an Akeley camera. Eventually, Akeley Motion Picture Camera became more than the research tool for which it was conceived. It revolutionized documentary filmmaking.

Film technology at the turn of the 19th century was bulky. Before Akeley’s camera, “tripod heads required left-hand cranking of two separate levers for each axis of movement, in addition to the right-hand cranking that advanced the film,” writes Mark Alvey in the 2000 edition of the Field Museum’s bulletin.

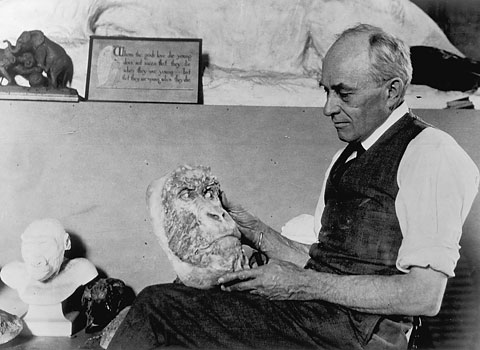

Akeley invented a camera in order to make his job as a taxidermist easier. Building dioramas was a job which required travelling to study animals, killing the animals, and then returning to the museum to stuff the animals and mount displays. On Akeley’s first expedition to Africa, in 1896, he was gone for a year and collected “400 mammal skins ranging in size from that of a rabbit to that of an elephant, about 1,200 small mammal skins, 800 bird skins and a ‘fair number' of mammal and bird skeletons,” wrote Patricia M. Williams for the Field Museum's 1968 bulletin.

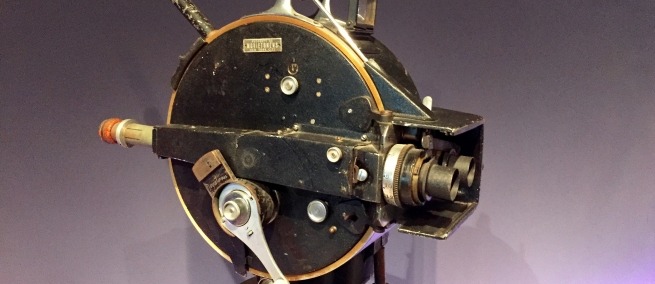

Akeley formed the Akeley Camera Company in 1911, and patented the Akeley Motion Picture Camera in 1915. (Akeley Camera Inc. was located at 244-50 West 49th Street in New York City.) The tripod he invented differs significantly from previous technologies because it is gyroscopically controlled, so that the cameraman could pan and tilt the camera fluidly. The camera was dubbed the “pancake” camera because it is circular.

By the 1930s, “the skills of ‘Akeley specialists’ were in demand–they were even listed separately on the American Society of Cinematographers roster,” writes Mark Alvey. The “Akeley shot” was written into film scripts to denote a shot of a rapidly moving subject in the foreground and a blurry background. “Although it eventually gave way to lighter and more mobile gear developed during World War II, the Akeley gyroscopic tripods continued to be used by major studios at least through the late 1980s,” Alvey continues in the Field Museum's bulletin.

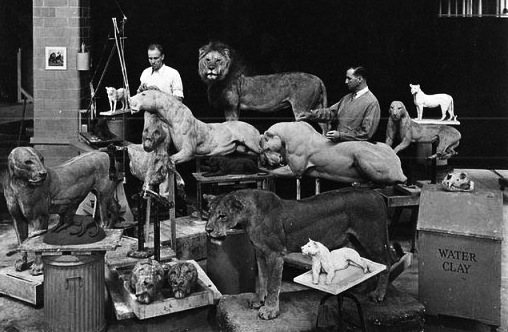

Akeley made films in the service of his taxidermy work, but he did shoot footage for the film SIMBA THE KING OF BEASTS, by naturalists Osa and Martin Johnson. The short opened in 1928 at the Earl Carroll movie theater in New York, and earned $2 million at the box office. After that, the Johnsons continued to use Akeley cameras to make some of the first nature films. A number of these films were funded by George Eastman, founder of Kodak. The Johnsons met Akeley in 1921 at the Explorer’s Club in New York, and travelled to Africa to make films of animals at his behest. Their films were endorsed by the American Museum of Natural History, even though they were partially staged. In Chanute, Kansas, the Safari Museum houses a collection of their photographs and films, and displays exhibitions related to their travels.

Akeley approached George Eastman for funding when he was planning the “Hall of African Mammals” now at the American Museum of Natural History. Eastman had just retired from Kodak and promised an initial gift of $100,000. Moreover, he went to Kenya with Akeley in 1926 to collect specimens, which included gorillas and zebra.

Akeley’s camera was used by news cameramen through the ’20s and ‘30, wildlife filmmakers like the Johnsons, and also by cinematographers. The pioneering documentarian Robert Flaherty used two Akeley cameras to shoot his 1922 film NANOOK OF THE NORTH in the Canadian Arctic. The film focuses on the daily travails of a family of Inuit–how they build an igloo, hunt walrus, and barter for knives with Arctic fox skins. The Akeley camera is relatively small, but still needs a tripod. Because of the gear, Flaherty had to stage some of the scenes in NANOOK OF THE NORTH such as the famous igloo-building scene. Flaherty also cast local people in roles–the wife of Nanook was really a woman with whom Flaherty was involved. Even though some of the film was restaged, he documented real phenomena and it is considered one of the first documentary films.

The work of Carl Akeley continues to be a major attraction at the American Museum of the Natural History, the Field Museum, and the Museum of the Moving Image. Akeley made his first diorama–of a group of muskrats–in 1889 at the Milwaukee Public Museum. He was the Chief Taxidermist at the Field Museum from 1896 to 1909. He moved to the Museum of Natural History in 1909. The Museum’s “Akeley Hall of African Mammals” has 28 habitat dioramas of which he conceived. The Museum of the Moving Image has an Akeley 35mm pancake camera on display in the permanent exhibition “Behind the Screen.” This particular camera was used by Dennis Bossone, a cameraman for Fox Movietone News, in the 1930s.

Todd Haynes’ film WONDERSTRUCK, which features Akeley’s wolf diorama, will be released in October of 2017. For more, read Science & Film’s interview with the screenwriter Brian Selznick.

Two field photographs courtesy Conrad Freulich and the Martin and Osa Johnson Safari Museum.