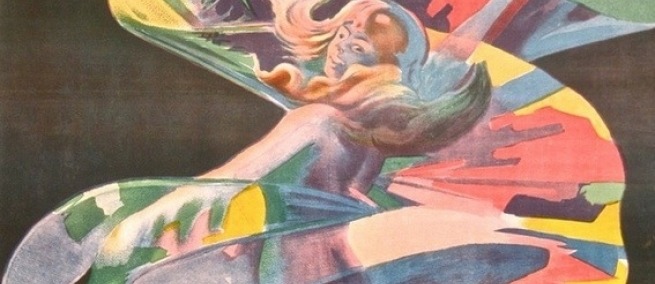

In Paris, the technology of artificial lighting had evolved from gas lamps to electricity by 1870. Life changed, and so its depictions did as well. Henry Tanner painted the Seine reflecting red electric lights at night in 1900. Electric lampposts posted on the Paris streets are lit in the evening of 1889 in a painting by Charles Curran. A woman reads by lamplight in an etching by Norbert Goeneutte completed around 1891. Sonia Delaunay’s dazzlingly colored geometries painted in 1913 were inspired by the Paris streets. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s lithograph of the dancer Loie Fuller illuminated with his gold and silver powder puts her in the spotlight. A short film by the French Lumière Brothers, who patented one of the first moving image cameras and made what is considered the first motion picture, is of Loïe Fuller dancing the Danse Serpantine in 1897. Fuller was the first to dance the Danse Serpantine, in which she swirled around various colored fabrics, taking advantage of the new spotlights and the film technology’s ability to capture light and motion.

These works are part of the 50 works on view in a new exhibition called Electric Paris at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Connecticut. The exhibition is curated by Margarita Karasoulas. A complementary exhibition at the Museum, Electricity, was developed by the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia and demonstrates, through hands-on activities, the scientific principles which underlie electricity such as positive and negative charges.

.jpg)

Karasoulas and Science & Film corresponded about the exhibition:

Science & Film: How do you see the Lumière Brothers' video fitting in with the rest of the Electric Paris exhibition?

Margarita Karasoulas: Loïe Fuller was a pioneer of modern dance and an early innovator in stage lighting. The film on view in Electric Paris shows how Fuller performed her famous “Serpentine Dance,” which she debuted at the Folies-Bergère in 1893. Fuller is represented in both the Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec print and PAL poster which conclude the show. Since Fuller’s dynamic performance is somewhat difficult to visualize, I thought it was important for visitors to see her swirling movements and use of multi-colored projected electric lights.

S&F: The Lumière Brothers are considered the first filmmakers, and filmmaking is a technology dependent on light. Were they an obvious choice to include in the exhibition?

MK: I wanted to use the film to help illustrate her performance – but yes, the fact that these filmmakers were interested in Fuller, the so-called “Electricity Fairy,” is probably not a coincidence! Fuller attracted the attention of numerous artists and filmmakers over the course of her career.

S&F: What do you hope people will learn from the exhibition Electricity that can inform their viewing of Electric Paris?

MK: Visitors to Electricity will come away with a deeper understanding of the science of electricity, and the interactives on display show how electricity works and functions. Those who see Electric Paris will discover how artists working in the French capital responded to and represented changing lighting technologies. When viewed together, both exhibitions will offer a fuller picture of the visual, social, cultural, and scientific history of artificial lighting in the nineteenth- and early-twentieth centuries.

S&F: What are some examples from the exhibition of the way the changing technology impacted the social life of Paris?

MK: This exhibition is about technological change and the role of artificial light in the making and transformation of modern Paris. But the issue of technological change more broadly is one that we can still relate to today. The answer here depends on the context: within the realm of the home, oil lamps, and later gas and electric light, permitted reading, socializing, and other kinds of activities in the evening. The advent of gas and electricity profoundly shaped urban experience. For the first time, people could travel freely and safely about the city at night, and the brightly lit boulevards, cafes, and illuminated storefronts contributed to the city’s vibrant nightlife, which we continue to associate with Paris today. Finally, in the realm of the theater (among other entertainment venues), these technologies revolutionized stage lighting. Without artificial lighting, such performances would not have been possible!

Visual examples of the impact of these technological changes can be seen in all four sections of the exhibition–– Nocturnes, Lamplit Interiors, Street Light, and In and Out of the Spotlight.

Carasoulas did a short filmed introduction to the exhibition:

Electric Paris is up now through September 4. Electricity is on view now through November 6. Both are at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Connecticut.