Jem Cohen’s latest film, LITTLE, BIG, AND FAR, has a contemplative flow that makes it easy to mistake it for a kind of biographical documentary about the heavens and those who study them. But the late-career Austrian astronomer, Karl, at its center is a fictional character (played by Frank Schwartz), and the epistolary style brings in the thoughts and journeys of Karl’s wife, Eleanor (Leslie Thornton), and a younger colleague, Sarah (Jessica Sarah Rindland). Cohen once directed a meditative film in a somewhat similar vein, MUSEUM HOURS, about a kindly guard, as well as the Fugazi documentary INSTRUMENT, among other works. Here he twins the musings of scientists figuring out their lives in a sometimes volatile world, with their ongoing studies of the universe in all its vast expanses.

The result is a movie that’s constantly feeling out the distances between stars and between people, while folding in the rich history and culture of the scientific pursuit. A trip that Karl takes to Greece reveals an unexpected resonance with the earliest discoveries of an ancient philosopher, and Sarah’s date with a young Ecuadorian astronomer, Mateo (Mario Silva), brings the film to the story of an abandoned telescope in New Jersey and then the history of scientists in the state after World War II. There are added meta layers to the film: Rindland and Thornton are both filmmakers whose work explores the sciences, and Cohen’s own young son supplies a remarkably detailed voiceover about the moon.

LITTLE, BIG, AND FAR premiered at the New York Film Festival and begins a theatrical run on July 11. I spoke with Cohen about the spirit of discovery and delicate web of emotional connections within the film; the real-life scientists that inform its fictional fabric; and how changing times have made LITTLE, BIG, AND FAR feel urgent in ways he hadn’t intended.

What led you to the character of Karl?

One of the initial primary concerns was to make a scientist character who was fully living in this world and having to deal with what we all have to deal with—but who has also spent their life teaching and researching, in a sense, in the stars. And I wanted there to be at least a few fragments of science that would be of interest to scientists, but of course, I was trying to make a movie for everyone. There are films that are specifically about activist propositions in regards to some crisis or problem, but I was trying to do something that was in a way parallel to MUSEUM HOURSin the sense that there the museum guard is a kind of fulcrum between the public and the institution. Karl, Sarah, and his wife, Eleanor, are all people who are in a sense grappling with how to live as research people and science people and museum people, but also people who have to talk science, who have to explicate to a broader audience, which is something that many scientists have to do.

There’s a new, existential urgency to the scientific pursuit and to museums in the current political climate. Was that on your mind as well?

Oh, very much. Museums were in crisis before Trump, in the sense that museums are generally speaking research institutions and so there's this extraordinary realm that the public doesn't encounter where the museums are actually doing art history or active preservation or scientific research. And museums were also facing the collective soul-searching that much of the culture underwent in regards to certainly race and gender, but also colonialism and history. What they weren't necessarily counting on was that they'd be catching hell from all sides. The threat is substantially worse now in terms of ignorance, funding removal, and the overall attack on scientific premise. What we're experiencing now is a basic retreat from scientific thinking as an understood necessity and a boon.

I didn't expect the film to be quite as pertinent as it has unfortunately become. I wanted to touch on all of these areas, but it almost pains me that people might think I made it a month ago trying to be au courant. I thought, “Are people going to feel like I'm overdoing it a little bit, when Karl has this rant about dark skies?” But things like fossil fuel expansion in desert areas are just a nightmare for observatories. And astronomers are pissed off about Starlink: it's fouling up their data and it's fouling up their observation.

But I don't like to make movies that are just about topics or problems or crises. What I was really most after was to maintain a sense of awe which is still primary for these people, for children, and for many people who are trying to maintain their sanity in dark times. Being able to take a walk in the woods or look at the sky or enjoy the bounty of these incredible space telescopes that are just doing the most mind-boggling imaging—these are immensely positive and mysterious realms. These are the most longstanding human concerns and therefore it's very natural that we feel the need to hold onto them.

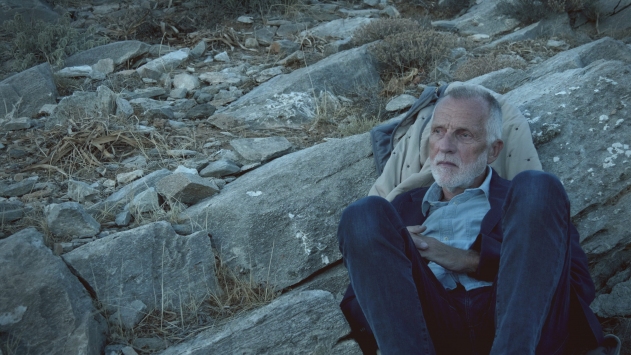

Still from LITTLE, BIG, AND FAR. Courtesy of Grasshopper Films.

Yes, Karl’s trip to Greece brings up the ancient Greek philosopher, Pherecydes of Syros. How did you come across him?

That was a no-brainer because he happened to be in the geography that I was shooting in by chance, and he possibly invented the sundial. But that whole territory of the earliest atomists and Lucretius and these other characters is utterly wonderful. It’s almost unbelievable that they were without the capacity to have any kind of direct observation of the microscopic, much less the subatomic, but they were already suggesting the possibility of everything being made of smaller and smaller particles. They got a lot wilder than that, and some of the ways in which they got wild are spookily spot-on. They're talking about the swerving of these particles and forces in a way that really sounds like they somehow were prefiguring quantum physics and uncertainty.

Karl and his fellow scientists explore an array of ideas in astronomy. What books and thinkers went into your preparation?

Well, I read a lot. An early spark was Janna Levin, who's the scientist in residence at Pioneer Works. Her books are wonderful. I read them all, but her first book, HOW THE UNIVERSE GOT ITS SPOTS, is quite special because it interweaves her personal biography with her explication of cosmology. That was quite important to me in thinking about preserving the human element but also touching on more complex scientific ideas. Carlo Rovelli is of course a wonderful touchstone for physics, because he's very down-to-earth and writes jargon-free books that are still deeply scientific. I read a few biographies of Einstein. I read a lot about people like [Georges] Lemaître—I still can't fathom that he remained a Catholic priest and came up with those pivotal notions of cosmology, and then was able to balance those two things. But I read a lot of things that are not in the film at all. I read a lot about Heisenberg, and there are people that I just read about because they were local Austrian people. I'm still reading physics stuff all the time just because I find it nearly impenetrable and I'm insisting to myself that I penetrate it to some degree! Really, for me, making the film is always a research project.

The film also opens up questions for the viewer in the best way.

I guess it would be fair to say that above all the film is about curiosity. And for me, this has to extend to the shooting and the editing, to try to embody these things. If science is so much about seeing the unseen or using instruments to reckon with the visible and the invisible, then how can you have some of that in the form of the film? I was hell-bent on avoiding some of the clichés that I think are often evident in films about science. There are a lot of wonderful ones, but I do sometimes wonder why almost every film that takes on the universe and its grander scale, or astronomy and its grander vision, has classical, perhaps grandiose music, or alternately new age music. To me, it was an early notion that free jazz was a really accurate musical parallel to what some of the forces of nature actually are—that insane balance between utter chaos and destruction, and constant creation and balance. I mean, it's just in the last 30 years or so that everything has changed with this realization that things are moving away much faster than they're supposed to be. Now they're going to know a lot more as they get a lot more data from the Vera Rubin telescope and the next step up in energy level at the Large Hadron Collider. All of these things could at any moment blow the doors off again.

The movie also explores the sheer human contingency of scientific discovery—how happenstance it can be for one team and not another to figure some phenomenon out.

Yeah, science is also riddled with failure and the things that don't get the Nobel prizes. You can't plunge into it without having a sort of tragicomic sense of accidental discoveries that jolted everything unimaginably ahead, and then the many things that were postulated and ignored. To some degree, it's a tremendous reminder of human frailty and the way in which like the industry's pendulum swing and some things get left behind—and then long after the fact, people are like,

“Wait a minute didn't so-and-so suggest that that might be what's going on

here way back when?”

In terms of imagery in the film, how did you choose that mesmerizing loop of a comet’s surface?

You can't beat that! A young Spanish amateur was harvesting the freely accessible data from these space missions, and he put together that little GIF. I just thought that it's incredible cinema. It was a pleasure to loop it and put it up against the Coltrane soundtrack.

Still from LITTLE, BIG, AND FAR. Courtesy of Grasshopper Films.

The spirit of observation in your film made me think of how art and science have a bond: they’re both empirical pursuits at some level.

Exactly, yeah. It's experiential and it's empirical. But there are also these aspects of life that stop everybody in their tracks that are hard to believe you're seeing. So they're simultaneously totally real and totally unreal. But not unreal in the way that AI and CGI are. The point that I'm making is that these phenomena are evident to us as humans with just the eyes and ears that we’ve got. And that as we step into this territory where it’s very hard to know what is manufactured in cinema and what is not, then it becomes a thousandfold more important to see things that are what the camera actually saw and what the cameraperson’s eye actually saw. When I work on a movie for seven years, I do a lot of standing around looking for a rainbow and hoping that a rainbow is going to come. I just felt like, yeah, it's pretty cool that we shot those stars with not very fancy gear.

Karl at one point reminiscences about his formative childhood experiences looking at the sky. What were yours?

I was oddly enough born in Afghanistan. I wasn't there for very long, but in those first years, I surely saw a good bit of unobstructed sky without knowing what it was. But I'm mostly a city kid. I took a trip out to the desert as soon as I graduated from college, just really wanting to see desert sky. When I saw the Milky Way for the first time and realized that you could actually do that, it's just incredibly good. And in New York, over the course of making the film, I would frequently just go up to the High Line where the amateur astronomers were often parked. And on a typical New York, can't-see-a-damn-thing-in-the-sky night, they're pulling in the rings of Saturn. It's just totally wonderful, and it's free.

♦

More from Sloan Science and Film:

TOPICS