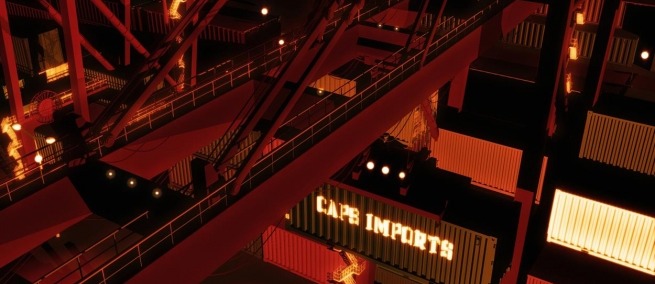

Multidisciplinary artist Meriem Bennani redefines how teleportation is depicted in her trilogy LIFE ON THE CAPS, which contains her short films PARTY ON THE CAPS (2018), GUIDED TOUR OF A SPILL (2021), and the 2022 eponymous finale. Unlike many science-fiction movies like LOGAN’S RUN (1976) and JUMPER (2008) in which every traveler is granted access to teleportation, Bennani envisions the political implications of traveling in a situation in which US troops monitor the borders by occupying the ocean enclave CAPS (short for capsules) and detaining illegal travelers. In response, the locals form a movement to resist militarization with parties and songs.

In her trilogy, Bennani also shows how people teleport not only to physical locations but to other human bodies. Actor Kamal El Jadid plays a fictional version of himself in the third chapter. His character seeks longevity by entering into many people.

LIFE ON THE CAPS has played at the Tate Modern, TIFF Wavelengths, and most recently at Prismatic Ground. We spoke with Meriem Bennani about interacting with many media formats, politicizing science-fused stories, and how new generations carry the past with them.

Science & Film: Your body of work across multiple mediums – such as animation, archival footage, and projection mapping – encapsulates the myriad of ways consumers interact with media. How has that led to the making of LIFE ON THE CAPS?

Meriem Bennani: There are many answers to this question. I spent a lot of time on different platforms, watching different subcultures that can emerge from YouTube and things like that, and observing how people use the internet [by creating] online personas. I’m interested in how people stage themselves. I'm interested in that kind of media production, where it's amateur – how someone creates a fiction of themselves based on what they've seen around them and personal preference. That's the big influence for the CAPS. But then there's also, like you said, the acknowledgement of all these references by using mixed media, like archival footage, CGI audio from different stuff, things that I make and take. In general, that’s how I like to work. It's like collaging and having references to different types of media languages and understanding what each language does best. So, if a scene makes more sense in a raw documentary style, like a verité, I'll go for that. If a scene makes sense as a reference to a wedding video, why not? It's really pointing at the emotional goal of the scene and what will make that work best.

Courtesy of the artist and Renaissance Society

S&F: It makes me think about escapism. Many science-fiction films tend to be escapist in their settings, like a fantasy. In LIFE ON THE CAPS, you show us that we can’t escape the reality we live in. How do you use art to confront current events?

MB: The work is based on reality. What it does though is it creates an extra step, not like an escape, but an extra step or a proxy through roleplay and sci-fi. Sci-fi allows you to abstract things. The people who are in my films are real people bringing themselves into the future. The roleplay aspect allows for playfulness that helps create the videos. It’s like a drug or an online persona where there's one more layer, then it's easier to play. Then maybe the truth comes out more than it would.

S&F: You also use animation and projection mapping. How does that enable the imagination and playfulness in your work?

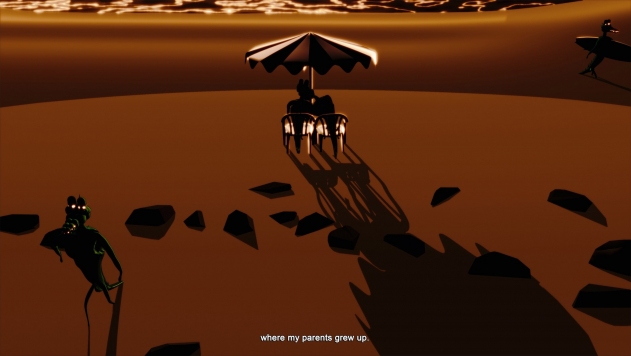

MB: The animation and the [projection] mapping have different functions. The animation happens in the editing process. Sometimes there’s as much animation as [live-action] footage, but it always serves a different function. It usually fills in gaps of things that didn't feel more fulfilled. Because in sci-fi, you need a lot of money to make some things believable. Through animation, I can do it on my own. I'm using animation for flashbacks. I've used animation a lot to create a narrator that allows me to be in charge of the storytelling out of nonfiction footage. So, the animation is my take on the footage that I shoot.

Then, there's animation that's overlaid on live action footage usually to point at something or make something familiar become strange, or change the tension that the raw footage has. I use projection mapping more when I do installations in institutional contexts where there's a bigger space, and I'm thinking about the site specificity of the work. All these things, whether it's the space, the mapping, animation, they're just tools for storytelling and blur the traditional narrative. In projection mapping, there are a bunch of screens. At first, you're not sure where to look and then you realize you have to develop your own mechanism for watching the piece, which tells us a lot about the contemporary experience of screens.

Courtesy of the artist and Renaissance Society

S&F: In many sci-fi works, teleportation tends to be depicted without many consequences or conflict. How do you see teleportation as a force of sociopolitical movement?

MB: I wondered how teleportation became political and [that was] a starting point for the story of the CAPS. I brought up the idea of teleportation to someone from the Global South. Sure we could travel faster, but would there be visas? That’s why I'm using teleportation [in the work]. It’s about borders and who's allowed to travel where.

S&F: Fiona the Crocodile glues the three films together. How would you describe her relationship to the travelers?

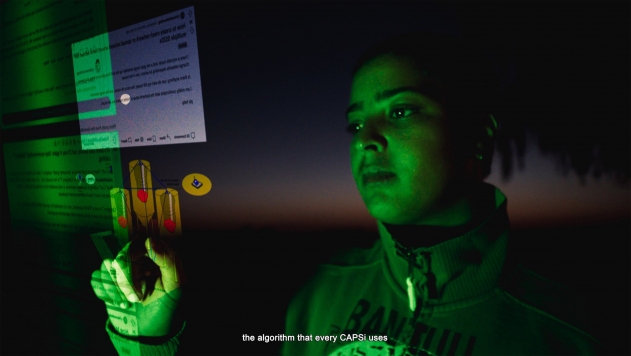

MB: I never thought about her relationship to travelers, but [rather] to the people who have been in the CAPS as they created the local culture. You never know if she is the narrator, or if she is an urban legend. Is she an algorithm? There’s a full narrative about her being like a cool, non-scary version of Siri where she is in everyone's technology. She grows with you and knows you. She filters what there is to see. It's a hard task, because the CAPS don’t have an internet open to the rest of the world. So, she searches through stagnant waters of data and tries to find things for you. But not in a capitalist way, more in a friendly way, because she's the product of what the capsules made for themselves. It's not militarized or against you. It's what technology was supposed to be, like progress. But she's also very traditional, like, ‘once upon a time.’ She opens things up and closes them off. She’s a tool for storytelling. She’s a symbol of unity [for the] CAPS. She's a mascot.

S&F: Your film touches upon reincarnation and longevity of one's physical existence, and the lineage of ideologies. How do you see the youth carrying information into the future?

MB: I don't know if I can answer this question because it's too big. But in the CAPS, there's a fantasy of return and the idea of people who are old enough that they're from the generation that wasn't born on the island, and now can't go back.

♦

TOPICS