The year 2020 was a moment of reckoning for race relations in America. The onset of the global coronavirus pandemic exposed our collective vulnerability while revealing gaping holes in our preparedness and responsiveness. Compounding the stress of the pandemic were perturbations of divisive politics, a contentious presidential election, ongoing socioeconomic concerns, unabating environmental and climate challenges, and renewed racial animus and struggles for social justice. For the particularly vulnerable, including communities of people of color, the compendium of calamities was that much more challenging.

The reinvigorated racial tensions of 2020 produced a notable upsurge in violence. High-profile killings of unarmed African Americans including Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, to name a few, set off a series of protests and refreshed calls for racial equality and social justice. This wasn’t the first time such events would take place, nor would it be the last. Rather, these instances reflected the complex reality of contemporary American social life. Even with the world as we knew it ostensibly falling apart– a critical time when we could band together to better ensure our mutual survival–we routinely resorted to division over unity, walls over bridges, bullets over books. Disillusioned, many were left to ponder, just how far had we actually come since the Civil Rights era of the 1960s, and how far do we have left to go?

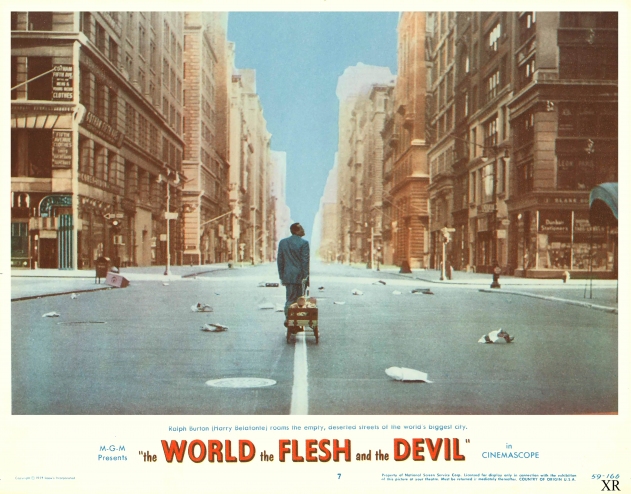

Historically, the arts have played a key role in helping society contemplate big questions. THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL (1959) is one particular film that sought to hold the newly desegregating America of its day to account. The film is of particular note because of how it makes plain the senselessness, yet peculiar persistence, of racial prejudice even in the face of global catastrophe and the existential threat to all humankind.

Ranald MacDougal’s THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL is a complex and ambitious film that combines the genres of post-apocalyptic science fiction and social message film to support an anti-segregation agenda. The film succeeds in relating the complicated interplay of social forces as a race drama. Through its representation and reconstitution of racial and gender identities in a fluid relationship to power, THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL’s ambiguous ending further illuminates the futility of racial segregation.

Harry Belafonte in THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL

THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL depicts an imagined, improbable, yet possible vision of the future in which nuclear technology annihilates world civilization. Harry Belafonte plays Ralph Burton, a black tunnel worker who gets trapped underground during a cave collapse in Pennsylvania. He digs his way out after several days to discover the world depopulated. Ralph learns from the headlines of abandoned newspapers that a nuclear blast has destroyed the Earth leaving him as the sole human survivor, or so he believes. After making his way to New York, Ralph encounters Sarah Crandall, a young, single, white woman played by Inger Stevens. Issues of race and the prospect of miscegenation rush acutely to the forefront of their rapport, as both Ralph and Sarah struggle with their affections for each other. As the film progresses, the expressed bigotry of a third survivor, Ben Thacker, performed by Mel Ferrer, further complicates Ralph and Sarah’s fragile relationship.

THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL cinematically and narratively bears elements of generic conventions from the science fiction and message film genres. The genre of science fiction cinema became very popular in the United States during the 1950s and acquired new salience in the context of the Cold War when concerns regarding nuclear war permeated American culture and politics. The development and use of the atomic bomb during World War II exacerbated social anxieties about the prospects of nuclear annihilation for several decades to come. Science fiction cinema in the 1950s thus generated nightmarish images of technological disaster, the apocalypse, and alien invasion, oftentimes as warnings against behaviors and pursuits that would lead towards such outcomes, but also as displaced apprehension about these issues. Another example of this phenomenon is Stanley Kramer’s 1959 post-apocalyptic film ON THE BEACH, which offers a thinly veiled warning against the arms proliferation and aggression between the West and the Soviet Union at that time. The film depicts the Northern Hemisphere ravaged by a nuclear World War III that kills most of the human population. The few survivors in the remote reaches of the Southern Hemisphere countdown their remaining days as a looming radioactive cloud encroaches to seal their doom.

Nuclear technology, the catalyst responsible for the post-holocaust state of the diegesis, serves as the causal base for THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL’s narrative. The atomic blast that eradicates humanity from the earth is the overarching impetus for the motivations and actions of the three characters in the film. The film does not visually represent atomic detonation or its consequent after-effects. Buildings and infrastructure remain intact, neither debris nor physical human remnants remain. Thus, the sense of vacancy and emptiness that results from THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL’s abandoned landscape helps focus the narrative on the human drama unfolding between the characters.

Inger Stevens in THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL

The Hollywood message film solidified as a genre in the 1930s and was produced actively into the 1960s. The message film addressed a range of issues including poverty and labor relations, postwar social and psychological readjustment, delinquency, anti-Semitism, and racism, often by foregrounding tensions between individual characters. THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL’s explicit treatment of race renders a snapshot of late 1950s social relations between blacks and whites in the United States, in the context of a burgeoning modern civil rights movement. It is a progressive commentary on 1950s US race relations.

In the setting of THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL, civilization is dead. Equally dead are all the institutions of civil society. There are no courts, no churches, no values or everyday codes of behavior. Despite this, Ralph Burton maintains his assigned social position as a black man, confined to a secondary societal status in a world that no longer exists. Without the constraints of segregated civil society, Ralph can seemingly act however he pleases, but deeply internalized pressures, proprieties, and expectations prevent him from transgressing social prescriptions. The psychic hold of racialization endures, even though the society that once determined such identities and hierarchies is no more. Ralph Burton is not just the last man alive; he is a black man in a dead white world.

Ralph is never freer than when he thinks he is alone. Once he accepts his new circumstances, Ralph slowly adopts the liberties of an emancipated subject. Now a free, unfettered individual, Ralph becomes the architect of his own destiny for the first time. With the social world absent, Ralph can live out his every fantasy. He establishes his residence in the penthouse of a luxury apartment building with breathtaking views of Manhattan. Ralph entertains himself with song, dance, and various home improvement projects. He fills the apartment with relics of civilization––sundry items including books, musical instruments, and a toy train set that wraps around the entire apartment. He also begins collecting works of art. Ralph’s actions not only express his desire to surround himself with objects of beauty, but also his need to partake in the cultural riches from which he had been previously excluded. In amassing various valued commodities, Ralph establishes himself as the primary conservator of human culture.

Inger Stevens and Harry Belafonte in THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL

Sarah Crandall’s (Inger Stevens) appearance in Ralph’s carefully constructed utopia destabilizes his delicate illusion of freedom and power. She is first revealed to the viewer through a close up of her feet in dark shoes surreptitiously scurrying after Ralph following one of his expeditions through the city. Sarah later admits that she had been observing Ralph ever since his arrival to New York. She explains that she was too afraid to come forward sooner, revealing Sarah’s own racial preconceptions.

Initially, Ralph and Sarah maintain their socially prescribed gender and racial assignments as male and female, black and white. They settle in different buildings, almost unconsciously reconstructing the barriers of a segregated order. With traditional gendered roles in place, Ralph attends to “manly” tasks like restoring electrical power throughout the city, working the radio and telephone technology to search for other survivors, and fixing things in their separate apartment blocks. Sarah oversees the domestic duties of maintaining the households and preparing meals. In one scene, Sarah bursts into tears at the realization that she will never achieve her life’s aspiration to marry, because she has no suitable prospects. Ralph consoles Sarah, promising to find her someone (else) to marry, thereby accepting the assumption that he himself is an inappropriate partner. In short, both Ralph and Sarah reproduce traditional race and gender codes. The constructedness of existing social practices are thus exposed in the starkest possible terms.

In time, the social demarcations of Jim Crow are challenged by Ralph and Sarah’s growing affection for one another. Sarah grows to respect and admire Ralph, while her womanhood engenders sexual desire in him. Yet her emphatic whiteness precludes any possibility of a shared future. Having fully internalized his racialization as the black Other, Ralph reconstitutes the notion of the exceptionality and sanctity of white womanhood and reproduces its subsequent overvaluation by re-imposing his relative exclusion from it. The resurrected ghosts of racial oppression and subjugation from his former life clash with Ralph’s yearning for companionship. He desires Sarah, but cannot have her. In his efforts to resolve this quandary, Ralph renegotiates his fantasy. He elects to create a platonic, desexualized, neutral place for Sarah within his environment.

Ralph employs his gendered and racial identities as black and male to dictate and enforce the exclusive terms of Sarah’s presence in his world. His routine rejections of her romantic advances demonstrate Ralph’s impulse to maintain strictly platonic relations with Sarah as a function of his internalized racialization. For example, when Sarah proposes to move into Ralph’s building so that he won’t have to do extra work to maintain both his and her residences, Ralph denies her request, briskly (and absurdly) replying, “people might talk.” Ralph’s response reveals the tenuous nature of his newly reconfigured, highly wrought, contentious identity––he is both the racialized, disempowered Other placed outside of mainstream society, as well as the default alpha male, empowered to dictate the terms of society.

The escalating tensions between Ralph and Sarah erupt in the sequence in which Sarah asks Ralph to give her a haircut. Visibly uncomfortable at the prospect of touching Sarah, Ralph makes a joke of chopping her hair off with a handsaw. The shot dissolves to reveal Ralph holding a proper pair of scissors, preparing to commence. After a brief pause, he carefully drapes a sheet around her neck to catch her hair as it falls. He fusses with the scissors. Sarah prepares for the cut by combing her hair into a desirable style. With a swoop of hair covering her eye she jokes through a hand mirror, “Remember, I’ve got my eye on you.”

Ralph’s profound discomfort causes him to fiddle and fumble as he slowly inserts his dark fingers into Sarah’s golden hair. At the start, Ralph conservatively cuts only snippets of hair. Upon Sarah’s insistence that he cut with confidence, Ralph exasperated, lops off large hawks of her hair. Stunned, Sarah watches the butchery through a hand mirror while Ralph indiscriminately hacks away.1 Ralph pauses in a close-up and tenderly blows away a lock of Sarah’s hair that had fallen onto his hand. He soon abandons the haircut and, frustrated, tells Sarah to cut her own hair the way he cuts his own. The uneasy couple endures a series of attractions and repulsions, enticements and rejections throughout the film. The mixed messages Ralph gives to Sarah are symptoms of his anxiety-ridden subjectivity.

Sarah attempts to recover from the trauma of her drastically altered image by offering Ralph another chance at cultivating their relationship. Clearly recognizing the sexual dimensions at play, Sarah in essence offers herself as a mate: “It’s taking you too long to accept things, Ralph. This is the world we live in. We’re alone in it. We have to go on from there.” Ralph rebuffs her attempt. Incensed, Sarah responds, “I know what you are if you’re trying to remind me.” Ralph’s disposition shifts from frustration and discomfort to defensiveness and anger. “That’s it alright…” he retorts. “If you’re squeamish about words, I’m colored. And if you face facts, I’m a Negro. And if you’re a polite southerner, I’m a negra. And I’m a nigger if you’re not!” Sarah sobbingly denies Ralph’s accusation of racism as he storms out of the apartment.

Inger Stevens and Mel Ferrer in THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL

Ralph’s claims to power are illusory and fleeting. They have slipped from his fingers like the lock of Sarah’s hair. Afforded the rights of the dominant male by virtue of being literally the last man on Earth, Ralph exerts only temporary primacy over Sarah, and strictly in gendered rather than racial terms. Ralph himself concedes that Sarah’s whiteness has trumped his assumed power position, demonstrating the internalization of racial hierarchy. He has so internalized his place, that the idea of touching a white woman unleashes a torrent of competing emotions––desire, terror, resentment, revulsion, and rage. Sarah’s ability to invoke, even unthinkingly, her proper racialized social positioning consistently disrupts Ralph’s utopian fantasy, and re-invokes the fractured nature of his subjectivity.

The untenability of Ralph’s power and agency is underscored further any time Sarah invokes her whiteness, ultimately reminding him “of what he is.” Ralph tells Sarah that the phrase “Free, white, and 21,”2 she flippantly utters in an earlier scene, “was like an arrow in my guts.” Sarah’s off-hand remark psychically penetrates Ralph and renders his attempts at self-determination null and void. One might also argue that the botched haircut Ralph gives Sarah serves as a misdirected retribution against white society for the emotional scarification of racial oppression. Sarah’s image, however, is only temporarily disrupted. She manages to recover her appearance and handsomely styles her hair in the scenes that follow. Also, her hair will eventually grow back. Ralph, in contrast, never fully breaks free of his internalized social positioning.

Ben Thacker, the third character in the narrative, arrives at a moment when Sarah is desperate for the intimacy that Ralph determinedly denies her. Ralph and Sarah first encounter Ben when his boat sails into the harbor. Ben explains that he traveled the southern hemisphere for six months looking for survivors. Weakened by exposure to radiation, Ralph and Sarah take care of Ben until he regains his health. Ben and Sarah soon strike up a friendship, while Ralph busies himself amassing further relics of civilization.

A self-proclaimed “ex-idealist,” Ben takes advantage of unobstructed access to Sarah and spends increasingly more time with her independent of Ralph. Meanwhile, Ralph keeps a watchful eye on Ben who bit by bit reveals himself to be an unsavory, self-important bigot. In one scene, Ben clumsily tries to woo Sarah, saying “Me man, you girl. How about it?” Offended, Sarah dismisses Ben, much to his chagrin. Irritated that his romance with Sarah has not developed they way he planned, Ben threatens Sarah with rape later in the scene: “I could force you. It would be easy. All the Boy Scouts out of town…Should I force you, is that the way?” Ben concludes that Ralph, not Ben’s own callousness, is the obstacle to his future with Sarah.

A rivalry for masculine and racial dominance develops between Ralph and Ben. The white masculinity Ben represents is another explicit reminder of the racial oppression Ralph knew in his former existence, and a direct threat to his sense of identity as black and male. Ben not only reintroduces the question of racial supremacy, but also poses the question of male dominance over the “prize” of white womanhood expressed through Sarah.

The introduction of a third party fully destabilizes and further complicates Ralph’s universe. Ben reclaims the power position granted him in his former life. This act of recovering what Ben assumes to be his rightful social positioning further contributes to the nullification of Ralph’s utopian fantasy of agency and self-determination––a process that Ralph has himself initiated.

Ben and Ralph’s bitter rivalry spills into the streets at the end of the film. Both men are armed and prepared to fight to the finish in a showdown over who will win Sarah. Ben hunts Ralph like an animal, positioning himself advantageously on the rooftops of the skyscrapers to shoot at Ralph scurrying through the streets below. As the battle progresses, Ralph passes by the United Nations building, where he reads the inscription “They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation shall not lift up sword against nation. Neither shall they learn war anymore.” Struck by the significance of the words, Ralph suddenly throws down his weapon and abandons the fight. Seeing the senselessness of the situation for the first time, Ralph confronts Ben and convinces him to discard his gun as well. Sarah, who has been trailing the two men, appears on the scene. She extends her hand to Ralph and asks him not to leave her. Sarah then calls out to Ben, and takes his hand as well. Hand in hand with their backs toward the camera, the trio walk off into the distance down the empty streets of New York and towards an unknown future, as the words “The Beginning” appear on the screen in bold letters before the final credits roll.

THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL opened in April 1959 to mixed reviews. While many reviewers felt that the film ultimately took on a tough subject and then failed to carry it through to a satisfactory conclusion, THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL still earned critical attention for its cinematography. Shot on location in New York City largely during early morning hours, the film achieved a celebrated look of desolation. Reviewers of the day singled out cinematographer Harold J. Marzorati’s vision of a post-apocalyptic New York City and Miklós Rósza’s musical score for particular praise. Although impressed by the actors, especially Belafonte, the popular press panned the film’s attempt at addressing race and integration. The film’s resolution, in particular, disappointed many critics and audiences.

Described as evasive by some and preachy by others, the film’s treatment of the race problem left many of its reviewers dissatisfied (Shaw 287-94). Several critics accused THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL of evading the very racial issues the film initially raised. The usually myopic and conservative New York Times reviewer Bosley Crowther wrote that “social distinctions and mating are considered in the most conventional terms and a potentially fascinating contemplation of a unique sociological change is discarded in favor of a cliché: two men and a girl on a desert isle…the evidence is that a good idea, good direction and good performances––at least by Mr. Belafonte, and Miss Stevens, to a lesser degree––have been sacrificed here to the Hollywood caution of treating the question of race with continuing evasion of more delicate issues and in polite, beaming generalities” (Crowther 35). Others echoed Crowther’s assessment, with critic Albert Johnson describing the film’s reductive interpretation of American race relations as “a wall of simple-minded cliché” that obscures social reality (Johnson 43).

Another objection raised about THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL’s treatment of race is the anesthetized representation of romantic intimacy between Ralph and Sarah. Although clearly in love, they never kiss. The only times Ralph and Sarah come into physical contact with each other are when Ralph cuts Sarah’s hair, when he lightly touches her chin in passing, and when Sarah takes Ralph’s hand at the end of the film. In this, the film echoed many other well-meaning social commentaries of the period.

Harry Belafonte had encountered similar limitations regarding romantic scenes with his white female co-star Joan Fontaine in Robert Rossen’s 1957 film ISLAND IN THE SUN; once again he had become involved in a project that failed to live up to its potential. Outspoken about interracial relations on screen and off, Belafonte, an uncredited producer of THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL again chastised Hollywood for its stagnant politics. At a press function in England in October 1959, Belafonte concurred with the detractors of THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL, stating that his own production retreated from a nuanced look at race relations and opted instead for gimmicky treatment of race. Belafonte commented, "Not only do I agree, but I said as much to Sol Siegel while we were making the film. And the protests of Inger Stevens and Mel Ferrer were even stronger than mine. But it didn’t do any good. They had a wonderful basis for a film there, but it didn’t happen" (as quoted in Shaw 290).

Yet even with the tepid exchanges between Ralph and Sarah, THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL stirred controversy in both the South and the North. One screening of the film in a segregated movie theater Fayetteville, Georgia in 1959 was stopped abruptly when the audience threatened to riot.3 The mere suggestion of an interracial relationship between Belafonte and Stevens’ characters enraged some members of the audience (Shaw 294-95), and so even with a forced ending, the film was still threatening to white audiences, especially in the South.

The ending of THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL is ambiguous. But, given the historical context of segregation, what other resolution could there have been in 1959? The system that legally sanctioned the segregation of the races was deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, only five years prior to THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL’s release in 1959, and some of what are now considered the defining moments of the modern civil rights movement had only recently transpired.

For example, the lynching of Emmett Till, a 14-year old boy killed by a white mob for allegedly whistling at a white woman, and the Montgomery Bus boycotts, both took place in 1955, and the integration of an all-white high school by nine black students in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957 preceded the film by a few short years. Lunch counter sit-ins and freedom rides were on the horizon in 1960 and 1961, and the struggle for equal rights was taking shape. The Loving v. Virginia Supreme Court ruling, overturning Virginia’s law against interracial marriage, did not take place until 1967. In fact, interracial marriage was against the law in at least thirty states at the time of THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL’s release. Given the socio-political realities of the day, it is surprising that the subject was tackled at all.

Hollywood’s own preoccupation with the question of racial mixing has an equally entrenched history. The guidelines of the 1930 Motion Picture Production Code, also known as the Hays/Breen Code, for example, prohibited depictions of interracial romance in cinema for nearly thirty years, beginning in 1924.

THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL ultimately disappoints viewers, both then and now, not because it recasts clichés or simplistically implies that one man can conquer all obstacles set before him. Rather, in the circumstances of 1959 Hollywood and American society, the film falls short because it is almost literally forbidden to embrace the logical climax the narrative builds towards. Ralph and Sarah, although in love, never consummate their relationship. The film opts not to risk the consummation that the conventions of the Hollywood love story call for. The hand Sarah offers to Ben immediately undercuts the hand that she extends to Ralph. The challenge of interracial intimacy gets repackaged as universal brotherhood, leaving the conflict between Ben and Ralph unresolved.

Yet despite the film’s narrative disappointments, THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL articulates an intriguing argument against racist politics, to say nothing of the film’s comments on the futility of violence; before they throw down their weapons at the film’s climax, Ralph and Ben are ready to start World War III on a smaller scale, in a battle which could potentially leave only Sarah alive, thus dooming the future of the planet. The ambiguous ending THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL offers ultimately illuminates the futility of racial hierarchy, and is arguably the only viable conclusion given the time the film was made. Thus, THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL’s historical context, combined with the film’s political overtones, accomplishes the film’s objective of underscoring the pathology of racial animus and illogic of segregation.

THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL’s final message from 1959 still rings true today, that of the biggest existential threats to humankind, the persistence of racial prejudice and social divisiveness can be counted chief among them. The film invites us to contemplate what will we leave behind when the world we know is gone. Will we overcome the perils of disunity and discord–can we afford not to? Shall we allow ourselves to embrace the potential of a new beginning, free of the arbitrary and rigid constructs that have constrained us for so long, or shall we concede to a demise of our design? What will be our legacy?

2.The expression “Free, white, and 21,” was a popular colloquialism in the 1950s, which dates back to the nineteenth century. It signifies someone who has the freedom to do as he or she chooses.

3. There was no indication in the sheriff’s report of the exact reason for the disturbance.

TOPICS