[Editor’s Note: This article is part of “Peer Review,” an ongoing series in which we commission research scientists write about topics in current film or television. Dr. Robert F. Garry is a Professor of Microbiology and Immunology and Associate Dean for the Graduate Program in Biomedical Sciences at Tulane Medical School, and his daughter Courtney Garry is in the Doctors of Nursing program at Johns Hopkins. We asked them to write about National Geographic’s six-part series THE HOT ZONE, starring Julianna Margulies, which is adapted from a book of the same name by Richard Preston. It is available to stream on National Geographic online.]

Filoviruses have been recognized as major threats to pubic health since 1967. Monkeys imported for scientific research to Marburg, Germany transmitted a virus to humans that killed nearly a quarter of the 31 animal handlers who were infected. Both Marburg virus and Ebola virus, which was isolated in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC, formerly Zaire) in 1976, have caused outbreaks with fatality rates up to 90%. National Geographic’s series THE HOT ZONE is a thrilling dramatization of the first-known incursion of a filovirus onto American soil. It is a highly entertaining series that offers a powerful reminder that the ongoing threat of emerging viruses must not be ignored.

In 1989, several monkeys (Cynomolgus macaques) at a primate holding facility in Reston Virginia, only 20 miles from the center of Washington DC, developed a fatal illness. As the disease caused by a filovirus now known as Reston virus spread through the facility’s monkeys, the facility enlisted the aid of scientists at the nearby United States Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) at Fort Detrick.

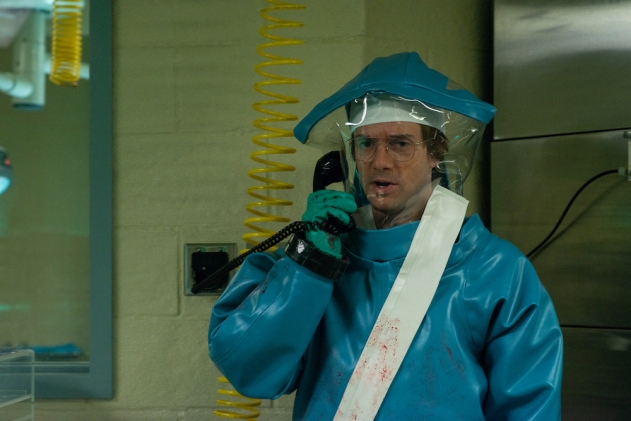

Still from THE HOT ZONE

THE HOT ZONE is based on the game-changing book of the same name by Richard Preston. Each episode begins with the notification that it is based on real events. This statement should also be taken as a disclaimer since the miniseries liberally mixes facts and fiction. If you are looking for an historical rendition of the events surrounding the Reston monkey deaths, you should read Preston’s book. However, the major storyline underlying the miniseries is accurate and the use of dramatic license is effective.

When the outbreak occurred in the Reston monkeys, the potential for a filovirus to spread into the human population of the United States was dangerously high. Diagnostic assays were available, but there was no mechanism in place for widespread testing. At this time, no drug or vaccine for a potent filovirus was available for emergency use. Only rudimentary plans existed to contain an outbreak of a highly infectious and often lethal virus.

Three-time Emmy award-winning actor Julianna Margulies portrays Lieutenant Colonel Dr. Nancy Jaax, a veterinarian who was one of many individuals at USAMRIID who responded to the potential threat of a filovirus outbreak near our nation’s capital. Margulies’ star power is evident throughout. She nails the demeanor of a dedicated scientist and the jargon of an experienced virologist. However, the requirement that a television event feature its star performer shifted the focus of events to Dr. Jaax, creating a simpler and audience-friendly narrative, but with some slights to others that played a key role in managing the Reston outbreak. For example, Dr. Jaax did not isolate the Reston virus. Rather, this was done by Tom Giesbert, then an intern at USAMRIID, under the direction of Dr. Peter Jahrling. As a veterinary pathologist, Dr. Jaax was not directly involved in virus isolation.

Liam Cunningham and Julianna Margulies in THE HOT ZONE

Besides Dr. Nancy Jaax and her husband Jerry (portrayed by Noah Emmerich), also a Lieutenant Colonel and veterinarian, many persons involved in the Reston outbreak are given pseudonyms in the miniseries. Another exception is Dr. Peter Jahrling, portrayed by Topher Grace. Those of us in the field of virology admire Dr. Jahrling’s sterling record of accomplishments. Except for this miniscule group, it is unfortunate that Dr. Jahrling will be perhaps be best known for smelling a culture flask in which Reston virus was being grown and enticing the intern Tom Giesbert (a version of whom is portrayed by Paul James) to do the same. In the end of the series, there is redemption of Dr. Jahrling’s character arc when he designs a new laboratory. In real life, it was decades later that the laboratory that Dr. Jahrling now heads was completed on the Fort Detrick campus.

As in Preston’s book, THE HOT ZONE does not hide the fact that scientists often make bad choices during outbreaks. In addition to the stressful conditions, fame seeking and career making can bring out the worst traits in individuals. Even Dr. Jaax is not spared at least one dubious moment: putting dead monkeys, dripping blood, potentially infected with a deadly virus, into the trunk of the car she uses to transport her kids to baseball games. In real life, it was head virologist at USAMRIID, Dr. Clarence James (CJ) Peters who transported the frozen monkeys in the back of his aged Toyota.

Two important characters in THE HOT ZONE are loosely based on USAMIRIID’s Dr. CJ Peters and Dr. Joseph McCormick, then of the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC). In a set of flashbacks, Wade Carter (portrayed by Liam Cunningham) and Trevor Rhodes (portrayed by James D’Arcy) track the Ebola virus during its early outbreaks in Africa. The portrayals of the impact of Ebola on villages represent some of the most poignant imagery of the miniseries. A scene of a burned-out village gives THE HOT ZONE audience a glimpse of the true impact of the disease in Africa. Missionary nurses and other caregivers are not spared its ravages. A trusted African Chief explains to Carter that someone always survives Ebola. This inspires him to understand that antibodies derived from survivors can become an Ebola cure, mirroring the use of monoclonal antibody therapies currently in experimental use.

Noah Emmerich in THE HOT ZONE

Unfortunately, the horrific consequences of an Ebola outbreak have not been significantly improved since the events of the 1980s depicted in THE HOT ZONE. With a focus on quarantine and patient isolation, Ebola patients often die alone having been given at best palliative care by over-worked attendants in alien-like protective garb. Healthcare workers still bear the largest risk of infection.

THE HOT ZONE is not immune to a few minor scientific errors, such as mispronunciation of filovirus (fai·luh·vai·ruhs) and the mistaken use of whole blood in the immunofluorescent assays (this was perhaps done purposefully to clearly show that a blood serum or plasma is used in such an assay.) Perhaps to achieve maximum dramatic impact or to simply provide a visual cue, the miniseries also misrepresents filovirus disease manifestations. Unlike patients featured throughout the series, filovirus-infected people do not develop blood-filled blisters on their bodies. The reality of filovirus disease is more frightening, because early in the disease course it is impossible to tell whether a person is harboring the virus. Filovirus diseases manifest principally as gastrointestinal illnesses; vomiting and diarrhea are the primary means by which the virus is spread, and other bodily fluids besides blood such as sweat (even after death) or semen can transmit the virus. If people actually did show blisters or other obvious signs of infection, outbreaks would be easier to bring under control.

Topher Grace in THE HOT ZONE

While the Reston virus does not appear to be highly lethal to humans as originally feared, the 1989 outbreak in monkeys was significant because it showed that developed nations are at risk for outbreaks of emerging viruses. The 2013-16 Ebola outbreak in densely populated West Africa infected over 23,000 people and killed at least 11,000. The ongoing Ebola outbreak in a conflict zone in eastern DRC has not, as of this writing been brought under control even with an effective vaccine and experimental drugs now available. Thus, THE HOT ZONE ends with a message that may seem pedantic, but must be heard. The world is still vulnerable and under-prepared. Much work remains to be done. Reactive approaches to disease outbreaks that rely on an influx of foreign responders have repeatedly been delayed, under-resourced and—ultimately—inadequate. There is an urgent unmet need for new proactive measures that are locally established, community-based, and rooted in reciprocal partnerships to address the challenges that viruses, including those that are as yet unknown, pose to global health and security.

TOPICS