[Editor’s Note: This article is part of “Peer Review,” an ongoing series in which we commission research scientists write about topics in current film. Dr. Christian Gelzer served as a technical advisor on Damien Chazelle’s biopic FIRST MAN, starring Ryan Gosling as Neil Armstrong. The film just won the 2018 Sloan Science in Cinema Prize presented by SFFILM.]

I have done some dangerous things in my life—swum drunk at night in a backwater where I knew crocodiles to be, tempted fate at Check Point Charlie on the wrong side of the border—but I do not routinely risk my life at work. Some people, however, do inherently risky work and must confront the real possibility of not going home at the end of the day. Research pilots, test pilots, and astronauts—including Neil Armstrong, who was at times each of these—are in this category. As the historian at NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center on Edwards Air Force Base in California, I was asked to be a technical advisor on Damien Chazelle’s biopic FIRST MAN because of what I know about Neil Armstrong’s history and technical abilities.

In 1955, Neil Armstrong moved from the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics’ (the NACA) Lewis Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio, to the agency’s High-Speed Flight Station (HSFS) at Edwards Air Force Base (AFB) in the High Desert of California. Neil had hardly been at Lewis six months before he relocated to fly exotic, challenging, and risky planes. Lewis (now Glenn) is still NASA’s principal icing research center, work that involves some of the more dangerous flying there is. Ice accretion on aircraft wings causes them to fly very badly, or suddenly not at all. Neil was a research pilot for the NACA, NASA’s predecessor, and at the HSFS he was eventually selected to be one of twelve X-15 pilots. Powered by an enormous rocket motor and launched (dropped, really) from beneath the wing of a B-52 bomber at 45,000 feet, the X-15 was the pinnacle experimental aircraft. Over nine years of operation, the three airframes demonstrated speeds close to Mach 7 (seven times the speed of sound) and altitudes above 60 miles. It was the first reusable space plane and eight of the 12 pilots who flew it earned their astronaut wings; it also claimed one pilot’s life and permanently shortened another pilot by nearly two-inches. This is the plane in which Ryan Gosling, who stars as Neil Armstrong in FIRST MAN, risks his life in the opening scene.

The survival rate in this line of work was not particularly high in the 1950s and ’60s: at Edwards Air Force Base the streets are named for pilots who died during flights at the base. There are a disturbing number. In the immediate decade after World War II, company test pilots were routinely given large, sometimes staggering, bonuses for making the first flight of a particularly dangerous aircraft. Companies, as well as branches of the military, sought to set new speed and altitude records. Companies would reward their pilots who set new benchmarks. And, of course, the NACA and Air Force had low-key bragging rights contests as well. Pilots of the X-15 left everyone behind with their altitude and speed records.

I was selected as a technical consultant on the film FIRST MAN in large measure because I had co-authored a monograph about the Lunar Landing Research Vehicle (LLRV), which Apollo astronauts including Neil Armstrong used to practice landing on the moon. My job on FIRST MAN was to make suggestions or offer corrections to various actions in a scene so as to maintain technical veracity. I made three trips to Georgia where most of the movie was filmed in order to advise on the scenes that featured Lunar Landing Training Vehicle (LLTV). I went first to Atlanta to teach Ryan Gosling (Neil Armstrong) what effect the controls in the training version of the LLTV had on the machine in flight, to show him what to do with his hands. My second trip was to the Georgia State Fairgrounds where, over two days, Damien Chazelle and his team shot elements of one scene: Armstrong’s ejection from the LLTV.

Fourteen months before going to the moon Neil was conducting a training flight in the LLTV when, in an emergency, he ejected from the craft midair. Much of that flight and all of the ejection was captured on film, now for all to see on YouTube. Although his parachute blossomed just 200 above the ground, he landed safely, suffering only a cut lip. Even today, nearly one third of those who eject from an aircraft suffer some permanent physical damage. Neil finished the day working at his desk.

My suggestions about this scene were always accepted. For example, a military pilot won’t search for the ejection seat handle in an emergency: it’s always between his thighs. Moreover, Neil was quite familiar with the action and reaction of ejection because he had left a fighter on short notice in combat.

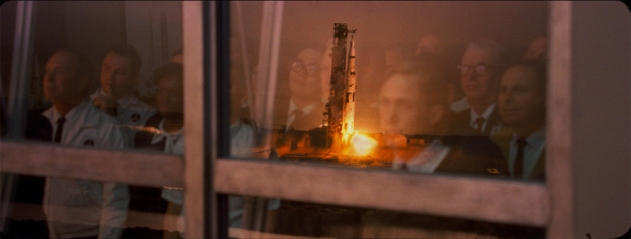

What was on the wall in the entry to the White Room, from which they stuffed the astronauts into the spacecraft? Sometimes it was a mounted fish. Is that six-degree-of-freedom simulator moving realistically? Not entirely. Was the top of the LLTV’s cab the same color as the underside? Yes—just a four-inch thick piece of Styrofoam. Director Damien Chazelle and crew were as technically accurate as film allows, something that pleases viewers regardless of profession. Crews built control room consoles by the dozen, it seemed: a Gemini capsule, an X-15 full aircraft and cockpit, an LLTV, a Lunar Excursion Module, accurate flight and space suits, a house, and more, all with careful attention to accuracy.

In 2017, in the Atlanta suburb of Roswell, sat a 1960s vintage ranch house with a pool surrounded by trees. It was a copy of the Armstrong house in Houston. I sat outside with Jim Hansen, whose biography of Armstrong was adapted for FIRST MAN and who is an associate producer on the film, and with whom I had taught at Auburn University. Hansen was almost always on hand to offer corrections: that individual wasn’t around at the time of the event portrayed, or Jan would not have used an expletive to Neil there. We watched a scene involving Jan Armstrong (Clare Foy): when things go awry on board Gemini VIII and NASA cuts the live audio feed, infuriating Jan. At one point, I leaned over to ask Jim what the family that owned the house thought of all this. Jim leaned in and before I could ask, quietly said: “You know they built this house from scratch for the picture.” I had to look around because nothing, not a thing, suggested this was so. “They must tear it down once they’re done and return the lot to its original condition.” The house had running water, electricity, functioning appliances and a Purdue pennant Neil acquired in college which he pinned to a bedroom wall and which the Armstrong family loaned the production.

My final trip to set was spent on set at the Tyler Perry Studios—a gigantic, newly-built complex on the former Fort MacPherson Army Base in Atlanta. The LLTV scene was behind me but questions about the X-15 remained. The filmmakers were in the hands of General Joe Engle, X-15 pilot and shuttle astronaut, and had General Engle been there they’d not have turned to me. He was there many times, just not the two days I was. Chazelle decided to take artistic license when filming Neil’s “long flight” to Pasadena in the X-15—the opening scene of the film—because he allowed the sun to sweep the cockpit briefly during an intense scene. This was one of many liberties the filmmakers took. In reality, Neil turned left to make it back to base, but in the film Chazelle had Neil turn right in order to get the sun to play across him. It’s funny: the filmmakers took liberties with one fact, but in doing so, made sure the new reality itself remained accurate. Chazelle used the “long flight” to introduce the idea that this sort of work weighs heavily on pilots and family. Neil and Jan’s daughter, Karen, died some time before this flight and the not-unrealistic supposition is that her death contributed to his Pasadena excursion, as well as decisions that followed. Neil, during this flight, bounced off the atmosphere and sailed right past the base.

Indicative of Damien Chazelle’s commitment to accuracy were the other two technical consultants on set while I was in Atlanta: astronauts Al Bean (Apollo 12) and Al Worden (Apollo 15). I caught Worden one morning sitting on a step leafing through a three-ring binder of the White Room procedures, where they stuffed the astronauts into the capsule, without reading glasses. We were standing next to two White Room scene actors when Worden asked one of them whom he was playing. The fellow no sooner answered than Worden said: “you used to dress me,” referring to the technician that the actor was playing who suited him up for spaceflight. A lively conversation developed about what the character was like.

FIRST MAN is, I think, a remarkably accurate rendition of research, test, and space flight and its inherent risks, possibly the best to date. The film reveals genuine tension amid underplayed bravado that these pilots, military or civilian, exuded. That tension, of course, ripples, and it’s not often told with such technical accuracy. Beyond the technical aspects, FIRST MAN is a story about the toll that doing risky things takes on people. We know from Hansen’s biography that Neil was, first and foremost, and engineer, not an explorer. “I think he was more thoughtful than the average test pilot,” said Mike Collins (Apollo 11). “If the world can be divided into thinkers and doers—test pilots tend to be doers not thinkers—Neil would be in the world of test pilots way over on the thinkers side.” Neil saw the trip to the moon as an engineering task that needed to be realized: he and Buzz Aldrin were merely the ones to demonstrate that the calculations and assumptions made about the last segment of a space mission to the moon were correct.

Armstrong and Aldrin were accidental explorers; they paved the way, and others followed.

TOPICS