[Editor’s note: THE CIRCLE is a new film directed by James Ponsoldt, and adapted from a 2013 book of the same name by Dave Eggers. The film stars Emma Watson as a new hire at a tech company, and Tom Hanks as its chief executive. The film is now in theaters. Science & Film commissioned Danielle Citron to write about issues of privacy and transparency. She did so with her 11th grade daughter, Eleanor Citron.]

In 1971, Professor Arthur Miller published The Assault on Privacy, which imagined a future of “electronic information nodes” recording every aspect of human experience. Society would be turned “into a transparent world in which our homes, our finances, and our associations will be bared to a wide range of casual observers, including the morbidly curious and the maliciously or commercially intrusive.” Computer dossiers would record everything about us, from womb to tomb, from grades and disciplinary reports, to purchasing habits and personality profiles. Being tagged as “inattentive,” anti-social, or unhealthy as a child would make later life opportunities difficult to obtain. Miller urged society to give careful thought before adopting technologies that would ultimately lock everyone–most especially children–into certain paths. Dossiers would become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Almost fifty years later, THE CIRCLE presents this reality in Technicolor. Private information is mined to provide a precise, quantifiable measure of a person. Everyone’s movements and pursuits are tracked and scored. The movie’s protagonist, Mae (Emma Watson), works as a customer service representative for a Google-like company whose name reflects its ruthless goal: to know everything about everyone—from health records to social interaction—at every stage in the circle of life. Every time Circle employees like Mae complete a transaction, “Circlers” are asked to rate the interaction on the scale of 1-100. Employees’ self-worth is defined by a seemingly omniscient numerical value on a screen. The hope is a perfect score for all to see.

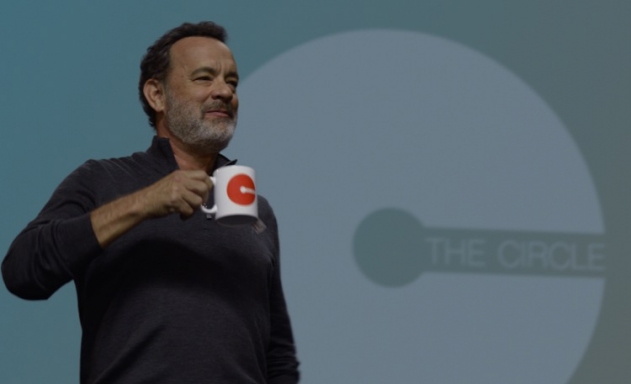

Social scoring is one of many methods of transparency pursued by the Circle. The company’s cameras, smaller than the size of an eyeball, are placed in all corners of the world. As the company’s CEO Bailey (played by Tom Hanks) promises, cameras will soon be recording every human action. The world will be totally transparent, and good riddance (says Bailey). The data has the answers—and in those answers we should trust. Seclusion and secrets are anathemas to truth and freedom. With cameras everywhere corrupt lawmakers, dictators, and criminals will be unable to hide their abuses. At the same time, the vulnerable will never be alone. Suicides will be impossible to commit because someone caring will always be watching. We are, Bailey argues, on the precipice of meaningful democracy and human connection. Privacy is so last century.

But to whom does transparency belong in the Circle? In Ponsoldt’s film, the ordinary person is the one being watched, followed, traced, scored, and rated. But this is not the case for the Circle’s top executives: they know everything about us but nothing is known about them. The Circle’s elites are the societal anomaly because they are neither surveilled nor understood.

That is precisely the world we live in today. We are totally transparent to the dominant tech companies whose platforms and devices know our every on- and offline activity, pursuit, and interaction. As THE CIRCLE asks in a somewhat cartoonish way: how much do we know about how our personal data is being collected, analyzed, rated, shared, and stored? Do we have any clue how our data is being used to manipulate and control consumers? How much do we know about the algorithms controlling searches, news stories, products, services, and content served to us online? The answer, regretfully, is hardly anything at all. The major tech companies have established a form of digital autocracy over all of us digital citizens.

Technological determinism has certainly helped this state of affairs. The view is: why not get the most out of our personal data if privacy is dead anyway?

Not so fast. As Professor Miller implored fifty years ago, and as THE CIRCLE brings to the silver screen, we are obligated to think hard before adopting every newfangled surveillance technology. We need to think through the implications of networked toothbrushes, televisions, refrigerators, toys, and clothing. We need to consider the implications of having cameras in stores tracking our every move so advertisers can meet our every need and whim (or rather manipulate us when we are most vulnerable). We must consider the promise and perils of technologies using personal data to score, rank, and rate individuals based on data and algorithms that reflect and perpetuate human bias.

As humans, we understand ourselves as having free will. As Sartre argues: we are living-breathing organisms, therefore we are free to make our own decisions. In contrast to Descartes's argument, “I think, therefore I am,” Sartre suggests, “I am, therefore I think” and “I am nothing, therefore I am free.” Sartre and Descartes seemingly reflect an antiquated view. We are not nothing, but rather we are a collection of things—algorithms, metrics, and data stored inside databases. We are not free because we are bound to our quantified past, present, and predicted future selves.

The film’s—and the book’s—precepts have become a universal truth. When we first read the book aloud to each other in 2013, one of us (Ellie Citron) wondered, “Is this the world that we will enter as grown ups? If that is the case, then I want no part of it.” And as the other one of us (Danielle Citron) said then, “not if we let it.” As we left the theater on a muggy night in April of 2017, we reminded ourselves of that conversation that occurred on a similarly warm and dark night in 2013. We need to keep reminding ourselves of just that—this does not have to be our future if we do not let it.

TOPICS