[Editor’s note: Science & Film commissioned Dr. Kevin Warwick, an expert on artificial intelligence, robotics, and neuro-surgical implants, to write about the technology in the 1995 film GHOST IN THE SHELL on the occasion of the 2017 release of a live-action remake starring Scarlett Johansson, which is in theatres March 31.]

We are transported into a world of the near future, 2029, in which an all powerful information network connects both technology and life forms into a collective whole. Those that matter, former humans, are connected into the network via cybernetic (part human part technology) bodies (shells) which give them superhuman powers but also rule their consciousness.

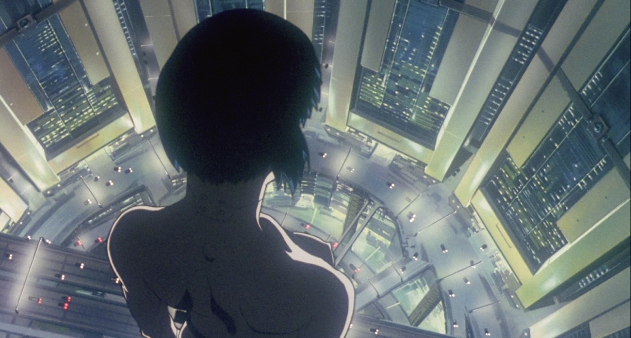

Such was the setting for the 1995 animated film GHOST IN THE SHELL, directed by Memoru Oshi and based on the manga by Shirow Masamune. Although it was produced by a Japanese crew, its setting was Hong Kong with its curious melding of the traditional old with the super-tech new. This same melding is directly reflected in its inhabitants of the future. The film explores many of the exciting yet frightening possibilities which are thrust onto the horizon with such an amalgamation. It also raises philosophical issues of identity, such as who or what am “I” if my brain is not my own? We hear the question: What’s a virtual experience? And the answer: All memories are false.

But along comes a hacker, known as the Puppet Master, whose aim it seems is to have some fun upsetting the status quo by implanting (ghosting) memories and thus characters. The intellectual Major Kusanagi, herself an augmented cybernetic human, is assigned to track him down, but when one doesn’t know who or what one is looking for it takes complex detective work. Kusangi uncovers the mysterious project 2501 in which the puppet master was created, transformed into a sentient being and then got into philosophical deep water by pondering its own existence, the meaning of its life and its inability to die. Ultimately the puppet master merges with Kusangi in terms of body and mind. So, Kusangi is both good and bad, a modern version of Stevenson’s Jekyll and Hyde.

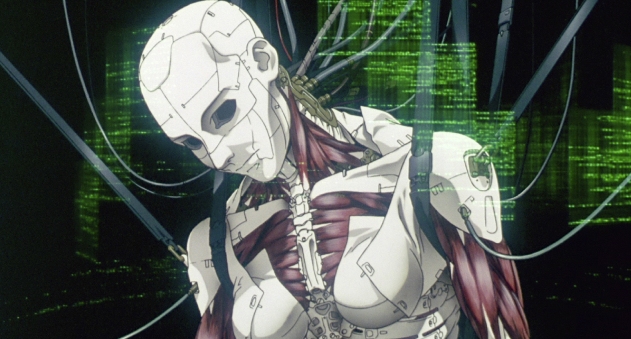

If this sounds like an unlikely scenario then you need to familiarize yourself with scientific progress. This is where I come into the picture as a Professor of Cybernetics with interests in Artificial Intelligence (AI), robots, and cyborgs (part human, part machine beings). Firstly, you need to get used to the fact that human brain cells can now be cultured in a dish, kept in an incubator at the right temperature, and fed. When the cells have connected with each other sufficiently (usually after ten days or so), they are given a technological body of which the grown brain is in full control and with which the cybernetic entity can move around and sense the world. Critically, such an entity can have senses, e.g. ultrasonic and infra-red, that humans do not have and a brain that is directly connected into a network, possibly the internet, where it can link directly with similar brains and trade information. While it is not yet the same size as a human brain, in terms of the number of cells, that is just a matter of time.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) can take on a number of forms. It can be computer-based or biological. Importantly, it doesn’t have equivalence to human brainpower as a limiting end goal. Indeed, as Alan Turing pointed out, because it is different therein lies its power. Already AI is much better than human intelligence in many ways, for example processing speed and accuracy, memory, the ability to operate in many dimensions (not just 2D or 3D), and the ability to take in a wide range of sensory input. On top of that, AI can learn, adapt and be far more creative than humans. You have to forget the antiquated cliché of a ‘programmed’ computer unless that is all you have. Only a couple of years ago the Turing test was passed, which means that a computer can successfully fool you into thinking that it is human when you converse with it. Most important of all, is that AI can be networked–it doesn’t have to be in one place, hence it can be much larger and much more powerful than human intelligence. Therefore, you cannot simply switch it off or close it down.

However, most pertinent to GHOST IN THE SHELL is the use of implant technology to link the human brain and nervous system to the Internet. This has been used for therapy to help paralysed individuals control a robot arm or to restore movement to their own limbs by, effectively, externally rewiring their nervous system. My own experiments back in 2002 are especially relevant. I had a BrainGate implant, consisting of 100 electrodes, fired into my nervous system where it remained for over three months for experimental purposes. With this in place we successfully brought about extra sensory (ultrasonic) input–I could detect objects whilst wearing a blindfold–communicated telegraphically (purely electronically) with my wife who also had electrodes implanted, and I was able to control a robot hand (prosthesis) in the UK directly with my brain signals when I was in Columbia University, New York City. I could feel the strength of the hand’s grip. In the latter example, it was really a case of extending my nervous system over the Internet–connecting me to an information network.

It is not surprising that a new, modern, Hollywood-style version of GHOST IN THE SHELL is just now being released in 2017. The story line appears to be roughly the same as the original as this time we have cyber brains (mixed machine/human/network) controlling prostheses in a world of information and data. However, the film is scheduled to be an action movie with Scarlett Johansson playing the part of the major. Naturally, AI has a bigger role to play, but the backdrop for the story hasn’t changed. Clearly our future will be inextricably linked to and with the information network. Whether it is the intelligent network itself that is in control or collective human brains acting as nodes on the network, we will just have to wait and see.