Dr. Anders Sandberg knows a few things about artificial intelligence. Having earned a Ph.D in computational neuroscience, he now works at Oxford’s not-so-humbly named Future of Humanity Institute, researching existential risk and human enhancement. But while still a teen in Sweden, Sandberg saw Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey on television, and was “hooked”. The film has gone on to inform many different aspects of his career, including his current research. Sandberg has returned to it over and over, and has found its nuanced depiction of artificial intelligence holds up over time. As Sandberg says, “Kubrick did something very important by making a protagonist who isn’t just a clanking robot walking around.”

Below are edited excerpts from Sloan Science and Film’s conversation with Dr. Sandberg.

AS: My first experience of 2001 was reading a synopsis in some kind of film review when I was very young. It didn’t sound like a particularly interesting film, just: “mad computer goes bananas.” That’s kind of pedestrian stuff if you’re growing up interested in science fiction. But later, it was shown on Swedish television and I watched it. For the first few minutes [I had] the normal reaction that I think most people have: what about these monkeys? What’s going on here?

Gradually, I was seriously hooked. It was totally awesome and very different from anything I had seen on television in terms of science fiction before. Or after, because I still think this is an unbeaten film. It’s sort of sad, actually, that it’s been around for so long and nobody has managed to come close to it.

SSF: What specific aspects seemed different to you from the science fiction you’d seen previously?

AS: One thing that I think was very powerful is that the monoliths are so different from any other strand of alien. You have something acting through some means that we can’t even perceive. It’s not the fake explanation you find in a lot of science fiction, where they say: “Oh, telepathic communication.” Which is essentially saying, “Oh, you got a cell phone call but it’s an invisible cell phone.”

There’s something very mysterious and powerful about it. Just like the monkeys would have had a hard time understanding a human tool, we have no idea exactly what’s going on. We see things happening, but we don’t know why or how they’re happening.

The other part that really hooked me was the technique. That’s the easiest part of the film to get into, actually: all the space transport, all the space equipment, which of course are famously inspired by a lot of ideas from NASA, taking blueprints and turning it into a very believable space science future.

As I’ve grown up as an academic and researcher, different parts of the film have appealed to me in different ways. One reason I started seriously reading up on mathematics was that as a boy, I wanted to make a spacecraft, and I realized I needed some of that to do it.

Now I work in cognitive enhancement; I’m interested in how you make brains better. And in a sense, that’s what the monoliths among the monkeys are. There’s some form of enhancement going on, there’s something triggering an evolutionary process. And at the other end, if you look at [Arthur C.] Clarke’s written story, he’s much more clear about what the aliens who made—or are—the monoliths were: that they started out organic and then evolved and redefined themselves into a post-biological form of intelligence.

That’s what I’m doing quite a lot of research about. I’m very interested in how we could copy brains into software. I’ve been working quite a bit on questions about alien intelligence. Maybe a lot of looking for Earth-like planets is completely missing the point. It might be that most aliens become post-aliens rather quickly, which means that we might have to learn to look for monoliths, and they’re probably not hanging around on Earth-like planets very much. It’s geologically unstable with an oxidizing atmosphere and not that much energy.

So the interesting thing is that there are parts of the film that both inspired me to get into certain areas of science and actually touch on my current research at the Future of Humanity Institute.

SSF: Can you talk a little bit about the Institute and the work that you do there?

AS: This Institute is the part of the Oxford Martin School that looks far into the future, at the big-picture questions. Essentially: “What’s the fate of humanity, and can we do something good about it?” So one part of it is looking at emerging technologies that might change what it means to be human. In particular, I’ve been doing research on the ethics of human enhancement. If we make ourselves live longer or become smarter, what are the consequences? What are the ethical considerations we ought to be taking into account? Another part is that we’re also concerned about global catastrophic risk and existential risk—things that could wipe us out. When we analyze that from a philosophical standpoint, it becomes very clear that many of these problems, from a moral standpoint, override any other consideration.

That leads to interesting questions about what risks there are. What can we do about them? And then of course, we have another problem: how to think clearly about these strange things that we know we don’t have all the information about? This is really where philosophers come in handy to help supplement what we can do using the normal hard sciences.

SSF: It does seem like HAL, the computer who is able to thwart its human masters, is the kind of thing that people are really worried will happen in the future.

![]()

AS: Yes, it’s kind of in the news right now. Our director [Nick Bostrom] just published a book called Super Intelligence, which is about the threat of very smart machines.

Most science fiction had been projecting standard fears onto something else, not actually taking them seriously as objects on their own. The idea of artificial intelligence had been surrounded, more or less, by good science fiction stories about dangerous robots and machines. But internally, A.I. research had not really been working much on safety and security. Most of the time scientists just said, “Yeah, yeah, but my machine is a bit too dumb to come up with any clever plan. Look at that industrial robot instead, it is heavy, it might squish somebody if we don’t design it well.”

Despite Frankenstein or Čapek’s R.U.R., no one was taking the risks of artificial intelligence seriously in the field until the late nineties. And still, of course, you tend to get annoyed looks or smirks if you bring it up at an artificial intelligence conference, because everybody who’s programming something knows very well its limitations. The problem is, of course, that when more and more of a system consists of connected and interacting pieces of software, that might generate a lot of emergent bad behavior, like the flash crash a few years back. Trading algorithms went haywire and caused an extremely quick stock market crash. There was no real intelligence there; they just behaved according to the rules.

It’s like the tragedy of HAL in the movie. HAL is just trying to follow its orders. It’s smart enough to try to implement them in the only way it sees as a solution. But it also lacks the human understanding of the situation. A human in the same situation would realize, “I have contradictory orders, something has to give,” and realize that killing off the crew is probably not the best solution. The problem is that if you happen to be a computer, its not obvious that killing people is worse than doing any other thing, like a trade exchange or baking a cake in the kitchen. They’re all equally possible options.

What we’ve been studying quite a bit is how you construct smart systems that are safe. That can realize, “I was ordered this, but that’s probably not a good idea. Maybe he didn’t actually mean that I should do that.” So the problem is that thinking about something that is smarter than yourself, and also probably constructed in an alien way, is very difficult. Again, this is an area that’s very underdeveloped but we’ve been working a little bit on the problem.

SSF: It seems like 2001 presented a pretty nuanced view of A.I. and humanity’s relationship with it.

AS: This shows how the film covers a lot of ground. When you see the things that are happening on the ship, it’s not a big problem really. It’s not a profound drama, it’s a computer reasoning and reaching a conclusion that happens to be, from a human perspective, the wrong one. And then you have an interesting cosmic perspective on biological intelligence. Where might we actually be going with the next step? After all, I think most people would say, if mankind could become the star child, that would be really good, except I have no clue what that star child actually is or what it’s supposed to do.

Why we should strive to become something post-human is an interesting question. It’s pretty obvious why we might want to live a longer, healthier life and have better control over our emotions and be a bit smarter. If we go on along that way we get to be something like Greek gods—it’s fun to be able to fly, but it’s still essentially human. But there might be other directions, things that are much more valuable.

We humans, we have philosophy, we have religion, we have science, we have various forms of art and sport and entertainment that monkeys cannot possibly understand. We can do it in front of them but they have no clue what’s going on and they definitely don’t perceive what’s fun about it, what’s good about it. And it could very well be that there are similar things out there that aren’t possible for our human minds, but if we managed to become star children or something like that somehow we would have access to this thing, and its just as good as philosophy, something out there that gives enormous value and meaning to life. We can’t know that before we try it.

SSF: That sounds sort of terrifying.

AS: That’s the problem with reasoning about things that we don’t just not know about, but that our brains might actually not be able to comprehend. That’s what I think is quite interesting both in the film and in the research we’re trying to do. How do you even point at these possibilities? That’s why the film is sort of subtle; you need to watch it and think about it to see some of these details. To me, the film really is about this question: where are we in the big cosmological scheme? We’re probably closer to the monkeys than the monoliths.

SSF: So do you think that 2001 was a science-positive movie for most people, or do you think it made them fearful of artificial intelligence?

AS: I think it’s a bit of mix. It’s very hard to make something inspiring that’s not also terrifying, unless it’s extremely sugary and sweet, and then nobody wants to watch it anyway. In a sense, the future shown in the middle part is rather sterile. It doesn’t seem to be an extremely happy place to be. At least aboard the spacecraft, it seems to be very boring. But then again, I don’t think daily life on the International Space Station is that exciting, either. I think most people would say that’s technology-critical. Except, of course, that the technology going on with the monoliths seems to be on a different level and I’m not sure how we can interpret that. We might be concerned about the violent impulses we see when the monkeys start figuring out how to use bones as weapons. That might be something necessary to move onwards. So in the end, even if you try deliberately to tell a story about how you should be careful about technology, quite often details will inspire people to become engineers anyway. Star Trek, for all its humanism, seems to mainly have got a lot of people to want to become engineers.

I don’t think it was a movie that got a lot of people to want to rush out and become scientists. But some certainly did. It wasn’t a movie that got a lot of people saying, “We should avoid high-tech, because it’s bad,” but some did. HAL became a part of our common consciousness: “Open the pod bay doors, HAL,” just as much as “Beam me up, Scotty.” But in the film it’s also a useful reference. How do you make your machines actually obey you? How do you make machines you can actually trust? One of the problems in the movie are these overconfident claims that no HAL 9000 has ever malfunctioned. If our cell phones were to claim that no Android phone has ever malfunctioned we’d probably be dragging them to court for making obviously false, misleading claims.

SSF: Yes, there is a certain amount of criticism in the film reserved for human hubris.

AS: In a sense, we put that hubris into our machines, too. Because what’s going on inside HAL is that it’s been given secret orders to do certain things and it gets more and more desperate to maintain the secrecy of these orders. You might argue that this is HAL’s misevaluation about how important the secrecy is, except what we’ve been seeing in recent years—in all these scandals about wiretapping—is that quite a lot of systems that are built based on secrecy lead to all sorts of weird misbehavior in order to protect that secrecy. And then you need to protect that weird misbehavior.

SSF: Is there anything you’d like to see in the science fiction of tomorrow? Depictions of artificial intelligence that would be useful in explaining to a layperson the issues we’ll be dealing with fifty or one hundred years from now?

AS: What I would love to see more of in science fiction is questioning how you take responsibility for enhancing yourself and changing yourself. Right now we have a lot of awesome technologies that are about to exist or are just starting to exist and we have no good ideas about the virtues of how to handle oneself with them.

Similarly, we’re all using smartphones but at the same time we’re getting used by the smartphones and the infrastructure behind them. How do you select these devices? It’s going to get more interesting because many of these systems are getting more and more anticipatory: building models of what we’re doing, trying to help us get what we want, and also make sure that advertising companies also get what they want. So choosing the technology you want around you and guiding it in a direction you think makes sense is one of the great challenges. How do you make a movie about that? Well, that’s tough. If I actually had a good idea I’d be trying to write the script immediately. But unfortunately I’m not a scriptwriter, and I’m definitely not a Stanley Kubrick.

Another part of my research is existential risk—actually getting people to understand how important it is and that you should have it as a serious factor of consideration and try to reduce it. The problem is that talking about the end of the world is a time-honored form of entertainment for us. Most of us don’t really take it very seriously. You might feel a chill run up your spine while reading about nuclear war or pandemics, but mostly it’s just talk of entertainment rather than actually reducing the risk. We’re underinvesting in making our civilization resilient. We cannot predict everything that could happen, but we’ve got to make sure we can reboot it if something crashes. We have to figure out good ways of keeping our information safe and we might need to be much more careful about developing certain technologies like artificial intelligence that could come back to bite us rather badly.

SSF: It’s sort of funny to hear you say this because often when you speak to scientists and science fiction filmmakers they make a point of emphasizing that these stories are parables for human fears, not practical possibilities. You’re almost saying the opposite, that maybe we shouldn’t be looking at these stories as parables.

AS: When Čapek wrote R.U.R., the classic robot story that coined the term, to a large degree that was a parable about slavery, although he was playing around with some of the aspects of having a real artificial thinking being. But what happens in 2001 is that the computer misbehaves not because it is chafing against its human owners. No, it’s just trying to do what it’s supposed to do, and that is the dangerous part. So I think taking some of these technologies seriously is worthwhile; not everything has to be a parable, sometimes cigars are just cigars. In this case, super intelligent computers are super intelligent computers.

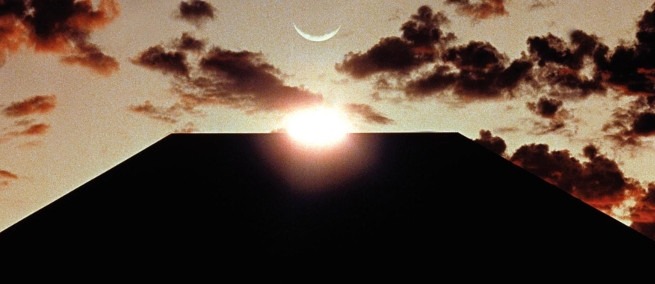

I think one last thing that’s worth pointing out is that 2001 is actually a beautiful film. We tend to talk so much about the meaning, but like any great piece of art, it’s also awesome looking. Not just the technical skill of making the zero gravity scene, but also the scenery with this perfect symmetry, with moons aligned, Jupiter and all of that. A lot of that is totally awesome.

SSF: Yes, it has that almost operatic quality, and it is very human because of that.

AS: When we say operatic we often mean something with a very strong emotional theme to it, and I think that’s true. It is a deeply emotional film, although it’s deeply emotional about something very intellectual.

SSF: Yes, that’s a good way to put it. That’s part of why it’s so challenging.

AS: It would be great if everyone could understand the film. But sometimes it’s also nice to have that sort of hard candy to suck on and chew on and really try to understand slowly.

SSF: Especially if you’re a super-scientist.

AS: Well, I think everyone can find something interesting in there to consider. Trying to figure out, “Yeah, where do we want our species to go?” That’s a good everyday question and that’s something we should be discussing over a coffee at least occasionally.