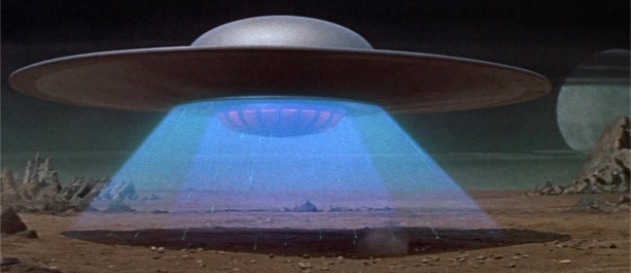

The familiarity of many of Forbidden Planet’s tropes—a man-made spaceship exploring the galaxy, a story set far from Earth, a robot as a supporting character—can make one forget while watching it today that the film doesn’t merely adhere to conventions; it introduced them.

Physicist James Trefil, Robinson Professor of Physics at George Mason University, was a child growing up in Chicago when it first hit theaters in 1956, and it helped him to see his predilection for science as more than a geeky hobby. Below, he references an essay by Isaac Asimov in which Asimov wrote, “Creative scientists are both born and made. The spark is there, presumably, to begin with, but it can all too easily be extinguished.” For Trefil, his encounter with Forbidden Planet helped to keep that spark going.

Below are edited excerpts from a conversation with Dr. Trefil.

Sloan Science and Film: Can you tell me a little bit about your career as a scientist?

James Trefil: I’m a theoretical physicist. Most of my research career was in elementary particles physics back when the quark model was just coming out. I got involved after that working with paleontologists on modeling the fossil record, and right now I’m focused on scientific literacy. I’m trying to explain science to people who are not scientists.

SSF: You mentioned before that Forbidden Planet inspired you. Why is that?

JT: In Forbidden Planet, there’s this idea of a very advanced civilization, with all this incredible knowledge, wiping itself out. I think that’s an idea that’s become very important since the launch of the Kepler satellite and the discovery that we live in a galaxy with more planets than stars. There must have been other civilizations out there as advanced as we are and maybe they wiped themselves out, too.

Also, the idea of converting mental thoughts into physical reality, which is the main conceit of that movie, is a very exciting idea. And of course, it had Robbie the Robot and all the rest of it.

SSF: Do you think that science fiction films inspire others this way?

JT: Isaac Asimov wrote this wonderful essay once, I think it was called “The Sword of Achilles.” It refers to an episode before the Trojan War where Achilles tried to hide in the women’s quarters because he didn’t want to go off to the war. So what the guys did is, they put this big pile of fabrics and stuff out on a table with one sword. And when the women came out and he picked up the sword, they had Achilles.

Asimov thought that science fiction was the sword of Achilles. It’s not so much that it makes people want to be scientists, but it kind of makes it okay for them to be scientists. Do you see what I’m getting at?

SSF: I think so…

JT: When you’re a kid, if you have this interest in science and the way the world works and exploring, science fiction, both written and on film, enables it and enforces it. It says, “This is cool, it’s okay to do this.”

I mean, look, I’m 75 years old and I still remember the message to Gort from The Day the Earth Stood Still. It does stick with you. These are good movies, they have interesting plots, and they have interesting ideas.

SSF: How did you end up going into your particular field?

JT: I had a lot of influences. I grew up in Chicago and having access to the science museums in the city was a really big plus. I had a very good high school chemistry teacher who was the first adult who told me, “Hey, kid, you’re good at this. You can do it.” But the most important part was discovering this other world, this very beautiful, peaceful world out there—that was very different from the chaotic life I was living, growing up in a blue-collar neighborhood in Chicago—and realizing that I could be part of it. The movies played a role in that.

SSF: Is there any recent science fiction you’ve seen that you think is doing a good job of inspiring the next generation of scientists?

JT: The whole Star Trek series— TV programs, movies and all that—it’s become much more part of mainstream culture now than it used to be. It used to be kind of off in a corner somewhere but now any kid you talk to in my classes, they’re going to know who Mr. Spock was, which is rather different than it was when I was growing up.

SSF: As someone familiar with important scientific trends, are there subjects you wish science fiction was tackling on screen?

JT: Okay, I’m putting on my scientific literacy hat right now. I would like to see much more about evolution. That continues to be a major problem in our society: the conflict between creationists and evolution. We could do more of that in science fiction and the movies than we do.

It irritates the hell out of my wife when we go to science fiction movies because I sit there and I tell her all the mistakes.

SSF: Looking back at Forbidden Planet and other films now, do you think they remain relevant?

JT: The special effects in movies have gotten so much better than they were then. But it’s sort of like going to a museum: the ideas are still powerful, I still like to watch them, but I recognize that a modern science fiction movie, a modern, say, Invasion of the Body Snatchers would be done today with much better special effects that would make it more visually impactful. But the ideas are the same.

SSF: As you said, the science in a lot of movies is not great. But do you think in the balance they’re still a positive force for kids the way they were for you?

JT: Oh, absolutely. I teach a lot of the freshmen physics majors, and in them I see a lot of the same kind of stuff that was in me when I was a kid. It inspires them. I come back to this idea that it makes it okay to be a physicist, which is kind of a weird thing to be if you think about it. The human mind does not naturally work in that direction, and so you need something that tells you it’s alright to be like that. I think if you go into any science department in any university that the majority of people grew up with one form of science fiction or another.

SSF: Are there parts of Forbidden Planet that continue to strike you?

JT: I think that monsters from the id was the real point of that [movie]. That no matter how advanced you get, you still have what they call the mindless primitive. That’s the message for human beings. I’m not in that kind of science, but that’s my observation as a person. That’s the greatest line from the movie. “Monsters, John… monsters from the id!”

TOPICS