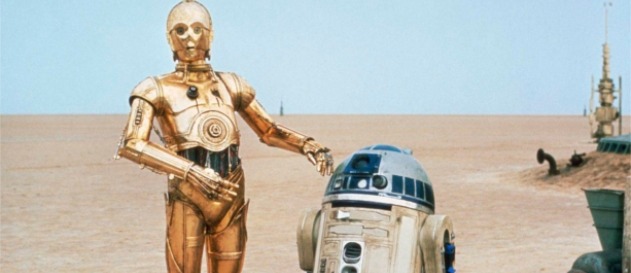

“R2-D2, you know better than to trust a strange computer!” C-3PO admonishes his robotic friend in The Empire Strikes Back, the second installment of the original Star Wars trilogy. The idea of computers interacting with one another may have been fodder for jokes at the time, but today, it’s easy to take for granted. Siddhartha Srinivasa, Finmeccanica Associate Professor in Computer Science of the Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University, was inspired as a young boy watching science fiction to explore the world of artificial intelligence. He explains that the robots of tomorrow won’t be strangers—they’ll be in constant communication with each other. A machine won’t have to “press an elevator button,” for example, “it will talk to the elevator and the elevator will open the door for it.”

Below are edited excerpts from a conversation with Dr. Srinivasa.

Sloan Science and Film: How did you get into robotics in the first place?

Siddhartha Srinivasa: I grew up in India and I watched a lot of science fiction. I watched all the usual suspects: the Star Wars movies, Star Trek. I grew up on a university campus surrounded by academics. We had this movie night every Saturday and I’d wait for the science fiction films and go and see them. I really grew up watching and reading a lot of science fiction. I read a lot of Ray Bradbury. Science fiction gives us a world that we can imagine to want to be a part of. That world is so beautiful that we want to make it real. And so we work on robots.

I was very young when IBM built this robot called Deep Blue, which actually beat Gary Kasparov, the chess champion, at chess. It was a pivotal moment because here’s one of the smartest people in the world, the best chess player in the world, and he’s being beaten by a machine. I was really intrigued, so I wrote my own little chess playing code. I really wanted to know, what does it take to be intelligent?

My chess-playing robot really, really sucked. It was horrible. It knew the rules but it had no strategy. I started doing self-play, where the robot would play against itself to get better. I got it to a point where it was not horrible, although it still wasn’t great.

That’s the essence of robotics: a system that is constantly learning, constantly getting better, through its own reinforcement but also through experience with the real world and demonstration and help from people. I do a lot of mathematics, but really it is about taking this idea of what is intuition, what is learning, and why do I pick up a coffee mug the way I do, and turning it into theorems and mathematical models and proofs that I can then turn into algorithms that go into a robot. I found that loop very fulfilling, this idea that you watch someone do something and ask why, and then you turn it into an algorithm and put it into a robot and it does that.

SSF: Can you tell me a little about he work you’re doing? I'm especially curious about your robot, which I hear is based partly on C-3PO.

SS: I work on getting robots to do physical manipulation tasks—opening doors, picking up objects, cleaning up—so it’s just as much Rosie the Robot as C-3PO. In some ways we’ve been very successful at getting autonomous technologies to perform passive tasks, like surveillance, but a big challenge is to get them to not just passively perceive and do intelligent, helpful activities but to physically interact with the world in the way that we do. Not just go from A to B and B to C, but to actually do something once you get there.

It’s incredibly challenging because a small slip and you could break [a] wine glass or drop something. Manipulation, when you fail, can be catastrophic. It’s incredibly complicated but in some ways I think it’s the future of robotics.

SSF: Why do you think that when we watch movies like Star Wars we think of robots as characters? They’re not very emotional but we anthropomorphize them. Is it because they do that type of interactive activity?

SS: I think there is something to these characters that makes them accepted even though they don’t display emotions in some ways that we do. It brings up a very important point, which is that functionality doesn’t necessarily imply acceptance.

You can build technology that is incredibly functional but if I want a robot in my home, I want it to not just be able to do stuff, but to also be able to understand the social context, to be expressive of its intentions, be expressive of its behavior. I think characters like C-3PO and Rosie embody that. They’re not just trashcans moving around performing tasks. They have some expressiveness in them that makes them all the more appealing to us. That’s something we really are excited about doing with our robots.

We have a robot, HERB. He’s got two arms that are on a Segway base, like a Segway you and I ride on, but it’s completely autonomous. He’s got a head, it’s got a bunch of sensors on it—lasers, cameras—and he wanders around performing useful manipulation tasks in our lab. We have a little kitchen environment and he microwaves meals and opens doors and stuff like that. It is really the future.

We do a lot of demos with our robots. Back in the day, if HERB was trying to pick up a coffee mug off a table, some people would pull the mug away from him. So then he would “fail” and they would say, “Haha, you failed!” I was amazed by this! I asked them, would you do this to your grandmother, would you pull a coffee mug away from her as she was reaching for it? And they would say, “No, of course not, but he’s trying to show off, he’s trying to prove his superiority.”

My robot is trying to do none of that. But the fact is that he doesn’t really acknowledge the presence of other people around him and act in a way that is respectful of their presence and subconsciously people watching him perform think that he’s snooty or arrogant. At that point I decided that we have to embody not just functionality, but also intent, expressiveness, even potentially emotive behavior into a robot if we want them to be accepted in our households. We’ve been doing a lot of research on how HERB can move in a way that is not just functional but also socially acceptable and expressive of his intent. He’s reaching for a coffee mug, but you need to be able to know that he’s reaching for the coffee mug even though his physical body—his kinematics—is not exactly like a human’s.

SSF: That is interesting because R2-D2 actually does sort of look like a trashcan moving around, but you can tell what he wants and what he’s doing.

SS: Exactly. This is why I love looking at movies and animation, because they embody so much character into these trashcan-looking things. If you look at Disney, for example, you can make a sack of flour seem sad, or happy, or angry, or anxious. I think there’s a lot of subtle behavior that is encoded in the minds of these animators and artists, and if we can formalize that into a robot then it could also not just microwave the meal, but microwave the meal happily.

SSF: How far do you think we are today from something like that? A robot in your home that can cheerily sweep the floor and ask if you want a drink after dinner?

SS: It’s not like there’s going to be nothing, nothing, nothing for the next twenty years and then suddenly there’ll be a HERB or a Rosie or a C-3PO in your home. The technology that we’re producing along the way—perception, machine learning, artificial intelligence, navigation—you’ll start seeing [it] appearing in your homes, in your offices, long before that. You’ll have smarter cars, smarter appliances. You won’t even call it a robot. Your car literally is a robot. It has so much technology in there and a lot of it comes from the field of robotics, the field of autonomy. So you’ll see pieces of HERB, pieces of this autonomous technology, appearing in your cars, your toaster oven, your television, your refrigerator, and you won’t even know it. It’s in some ways setting the groundwork for when an autonomous agent can actually enter this environment.

You and I might not want a robot that takes twenty minutes to go fetch us a drink, but there are people—paraplegics, quadriplegics, people with high spinal cord injuries—for whom, if they drop their TV remote, they can’t pick it up and they need to call a caregiver. So for them, having any technology that can enhance their quality of life and enhance their independence, even by a little bit, is a huge win. These are the people who are going to be the early adopters of our technology.

SSF: If you look at Star Wars or Rosie the Robot, that seems to be the game plan. But it does seem like there’s been a shift when you look at Battlestar Galactica or The Matrix or other dystopian movies where the robots rise up and kill us all.

SS: I think there’s always been that dark side to technology. We’ve had the good robot and the bad robot: Metropolis and Rosie, and now Battlestar Galactica and Wall-E. Technology, as we have realized in the recent past, can be used for good and can be used for evil. I think it’s important that we not only develop the technology but also develop the legislation and also our own social consciousness so that we can accept this technology. I have no doubt in my mind that we will have robots in our homes, in our offices, living around us, in the future. And we’ll have to answer a lot of these questions. For example, if you look at autonomous vehicles, it’s not a question of if an autonomous car will run over a pedestrian, it’s a question of when. There are hundreds of thousands of accidents that happen every day, and robots are good, but they’re not so good that the number of accidents they’ll have will be zero.

Also, the focus on the darker side of robotics and artificial intelligence probably has come about partly because we’ve shown such improved capability. When people see this technology that seems superhuman, some of us see the positive potential of this, but some people are terrified and see the negative potential. I think it’s both. We’re reaching a state now where robots are better than humans at some things—way better. And they’re way better than humans at some things we thought we were really, really good at, like chess or Jeopardy. It’s inevitable we feel threatened. [Shows] like Battlestar Galactica are reflections our own personal insecurities about technology.

SSF: So what’s your favorite depiction of robots on screen?

SS: There was a very recent, very small movie made called Robot and Frank. It’s about this old guy whose son gets him a little robot to hang out with. I felt like it explored a lot about aging, about loneliness, and I also thought it featured depictions of technology that I can imagine being real in the future. It was very appropriate, very touching, and raised a lot of interesting issues.

SSF: Looking forward, is there robotics science fiction that you’d like to see?

SS: If I were a science fiction writer, here’s what I would work on: One thing that is very, very interesting to me is this notion of memory. Humans, we forget; we only have a limited memory. But robots never forget. They remember everything. Our robot, HERB, he has been operation for several years and he has logs of pretty much all of his existence, which means he can go back and replay almost exactly what he felt, what sensors he felt, what sort of experience he had, and how he moved, from two years ago. I don’t know how that would be. I think one of the reasons why we forget is because it’s better to forget certain things, positive and negative. Imagine if this robot were in my home and as I grow older, it doesn’t grow older. It doesn’t forget. I don’t know how I would feel. I don’t know if I would ask it to recall my memories for me or whether I would want it to forget.

The technology that we have around us is giving us, indirectly, this ability to never forget. I have my emails that I sent to my wife when we were dating eleven years ago, and every once in awhile I go back and see them and we’re both transported to this time when we were young and carefree. This kind of technology didn’t exist twenty years ago. As we get more and more into a state where there’s so much data that you’ll never forget it, I think it has interesting ramifications for our own lives.

SSF: What’s it like being around a robot like HERB?

SS: I built this robot from scratch and we’ve been together for the past eight years, my students and my robot. It almost feels like part of our family. Sometimes I walk into the lab and my robot has learned something new on its own. And it’s amazing. It’s like watching—I have a two-and-a-half year old son and whenever he learns something he’s happy, I’m happy, everybody’s happy.

[Robots] can be truly autonomous, they can learn over time, and it’s a very uncanny feeling to walk into work and realize, huh, my robot learned to pick up that coffee mug. I never taught him that, he just tried it a bunch of times and figured it out. That gives me the chills sometimes, like what else is he going to learn next? Sometimes I worry he’ll get way smarter than me and won’t want to be in my lab, and one day I’ll show up and he’ll have left me a little note saying, “Sidd, you’re really boring, I want to go explore the world.” But it’s really an exciting time to be working in robotics, I think. We’re slowly living up to the promise of robots everywhere, doing useful things.

TOPICS