Without realizing it, we seem to be living in the Golden Age of dystopias. Glance at the rather unthorough Wikipedia entry for dystopian films, and you’ll see that more have been made and released in the last dozen years than in the previous hundred. (The list still leaves out scores of recent qualifiers, including Enki Bilal’s Immortel ad vitam, from 2004, and micro-indies like 2006′s Numb and 2010′s Zenith.) Certainly, although dystopian fiction has been popular since the 19thcentury, more people are reading it now than ever, most often in the spawnings of The Hunger Games-inspired YA. Science fiction is a cultural application with many functions—neurosis vacuum, dread volumizer, satire perpetual-motion machine, Frankenstein-ethics thermometer—but dystopias may be our most exposed confessional, the paradigm with which we most nakedly pick the scabs off the socially-transmitted present-day lesions we are otherwise loathe to acknowledge. So if it’s a genre du jour for the 21st-century’s Millennial Post-Adolescence, what is it that’s being probed?

That’s easy: consumerism. Consumerism as mind control, as mass addiction, as generalized virtual thrall. In real life, it has become self-evident that we are evolving, from being merely hungry bags of jelly and enamel eating other growing things for survival, to being individual teeth and taste buds and sparking synapses belonging to a conglomerated consumption beast, whose task it is to engulf and absorb everything, because it is self-justifyingly glorious to do so. This new us is fraught with ambivalence, and as a society we are both vexed and enraptured by our enslavement to convenience, material acquisition, and entertainment. It’s inevitable that dystopian film narratives would pounce on this reality, even if they began somewhere else altogether: the subgenre started in the post-WWI era as a hyperbolic expression of class-war fury and of terrified anti-Communism. In fact, the dehumanizing triangulation of industrialization, Communism and Fascism, and their particular forms of top-down oppression, became thereafter foundational elements of what a “dystopia” is. (In the 19th century, and going back to Swift, the anti-utopias were less politically structured, and more apt to form their social disasters around simple human foibles, like xenophobia, greed and vanity.) Starting on film with Lang’s Metropolis (1927), and proceeding onward to the weak-kneed British version of George Orwell’s 1984 (1956), dystopian films were a way to ponder how in the hell huge swathes of humanity got themselves into this strange and elaborate kind of maddened, self-destructive trouble.

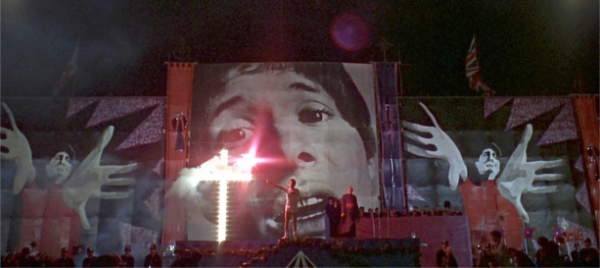

It remains a question worth asking. But by the 1960s—in sci-fi fiction by the boatload, and in cinema by way of Elio Petri’s The 10th Victim(1965) and Peter Watkins’s Privilege (1967)—the inquiry about how, exactly, the oppressive state-and/or-corporate forces at work retain their hold on their downtrodden populations turned to a villain suddenly looming in the nascent days of broadcast television: entertainment. Not just old-fashioned time-killing entertainment enjoyed in a vaudeville house while you drink, chat and play cards, but middle-class mass entertainment you devote yourself to, passively absorbed mega-entertainment that finds meaning in your life sheerly by dint of its hypnotic, artificially contrived, electronic-media glamour. Movies, as semi-theatrical events for which you purchased tickets, were bad enough, but television was entertainment you didn’t buy—it bought you, and then sold you. You were the floor cleaner, the two-door sedan, the pack of Chesterfields. We did not merely like the experience of being bought, sold, guided and gulled, we loved it, as sheep love their herding. Doubtless, the undeniably chilling spectacle of prone viewers gaping slack-jawed at a living-room TV compelled many a writer and artist, who’d never seen such behavior before, to wonder how this level of consciousness control may be used opportunistically in the future.

Cut to the present: as mass entertainment has come to subsume all other culture, and as the technology industries built to deliver this cataract grow and overshadow other sectors (including areas like food production and housing, which actually sustain our real lives), our dystopias have become preoccupied with the poisonous reign of consumerism and media preoccupation, from the prophetic advertising assault ofMinority Report (2002) and the devastating Big Box post-apocalypse of WALL-E (2008) to the televisual bloodsport of The Hunger Game series (2012-2015), the virtual-media subworlds of the Resident Evil films (2002-2012), and the contextual universes of Southland Tales (2006), Gamer (2009), Surrogates (2009), In Time (2011), Total Recall (2012), Antiviral (2012), Dredd (2012), Cloud Atlas (2012), The Machine (2013),Elysium (2013), RoboCop (2014), and so on, plus an uncountable proliferation of Japanese anime. EvenThe Matrix films (1999-2003), if you squint, entail a virtual echo-verse that mercilessly diverts as much as it mercilessly enslaves. Ray Bradbury, writing in 1953′s Fahrenheit 451 about Linda Montag’s addiction to the virtual interactive “Family” on her wall-sized television screen, may have been the new order’s first true prophet. In this modern incarnation, the dystopian power still emanates from above, but instead of using threat, torture, paranoia, Thought Police and labor camps—the Soviet model, vociferously feared by Orwell—the methodology caters to our most indulgent and thoughtless appetites, and our persistent desire for escape, which is the American model, now recognized by social planners to be by far the most effective. Aldous Huxley, living in southern California for the last 25 years of his life, always knew that no other apparatus would work as well, and therefore it was the paradigm to fear.

Welcome to Huxleyland. In these moviescapes, we are kept docile and profitable, or at least consistently distracted from the business of government and commerce, by our dolorous commitment to media and the addictive actions of consumerist satisfaction, brand fanaticism and the tribal “liking” of agents and products. If that sounds like it might be cutting too close to the 2014 bone, consider how succinctly Sidney Lumet and Paddy Chayefsky’s Network (1976) made that same point land in your skull almost four decades ago, and without recourse to futurism per se. All of which begs the suggestion that “dystopia” is no longer a science fiction subgenre at all, but the quotidian reality we live every day, controlled by a commercial schema of luxurious diversion so scrupulously devised and erected that we cannot see it. Its monstrous forest-ness is obscured by the multiple screens in our hands and on our walls, by the streams of persuasion and deflective noise budded into our ears, by the flood of input compelling consumption in the future and permanent desire in the present, even as it collates our data and individualizes its messages to us. We’ve met dystopia, and it is Google.

Or the Internet in toto, which I can easily imagine expanding its dark-and-light selves exponentially until, soon, a tipping point is reached, the global matrix coalesces into a sentient being, in a microsecond it realizes it controls absolutely everything, and simply takes over the world for real. In the meantime, helplessly, because we are happy consumers, we soft-pedal Armageddon. The contemporary eruption of dystopian fun we’re seeing may lampoon high-tech consumerism and entertainment enslavement, but no one is made to feel bad about their participation. Honestly, how the millions of Americans who saw WALL-E didn’t walk away chastened and embarrassed by their Costco bills and Big Gulps and aeons of couch time could seem a mystery—if you overlook the simple fact that the speed, lightness and beauty of Hollywood moviemaking does a superlative job at turning us into the satire’s compadre, not its target. It’s always someone else’s civilizational suicide.

So, in a textual turnabout too obvious even to be griped about, dystopian entertainment becomes what it beholds, a marketable amusement among many, a symptom of the disease, no longer a diagnosis. Look to The Hunger Games films to see the ideological struggle at work: the social-science fictional elements are quickly and resolutely subsumed by action-movie heroics, predigesting the dystopian steak for us and feeding us only the pablum of fireworks, sexiness and comic-book triumphalism. Consider as well the remakes of RoboCop and Total Recall—unlike the Paul Verhoeven originals, which were seriously vicious about the complicity of entertainment media, the new movies hone in on chases, CGI and video-game imagery.

Like Kurt Cobain’s loathing of corporations colliding with Nirvana’s corporate-marketed breakout fame, this conflict is bound to end badly—that is, with the very notion of dystopia watered down to a variety of “fantasy,” sold in bulk and with the vestigial teeth of social commentary removed. Dystopias have always been a form of critique, but as their visions become both increasingly realized as fact and diluted into spectacle in the very media they once were purporting to skewer, they may become something else altogether—just another bonbon proffered for our blissful consumption. Anything can be sold to us, and through us. Even the machine itself.

TOPICS