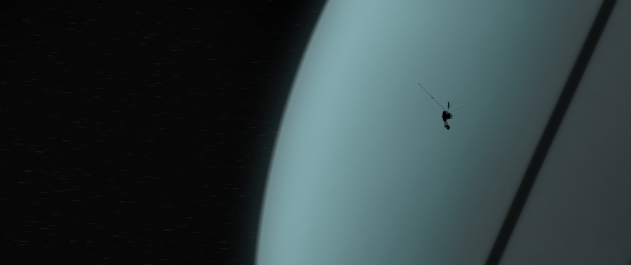

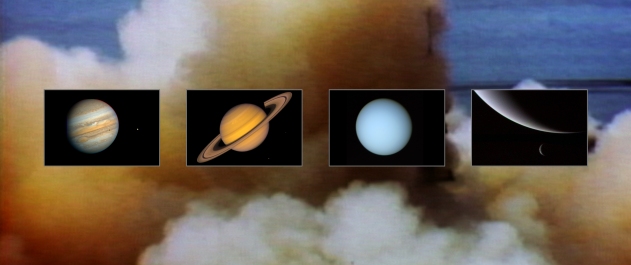

The new documentary THE FARTHEST follows the Voyager spacecraft as far as interstellar space. The spaceship, which turned forty years old in 2017, has travelled 12 billion miles. THE FARTHEST, which made its United States premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival, culls from thousands of Voyager’s original photographs of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

Launched by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in 1977 under the Nixon administration, the two Voyager spacecrafts each carried a gold-plated record, called the Golden Record. The record was produced by famed astronomer Carl Sagan (COSMOS) and contains images and sound recordings from cultures across the world. The Golden Record is now available to stream online. It was sent to space in the hopes that any life that was out there would intercept and learn about us.

THE FARTHEST is about both the Golden Record and the scientific mission of Voyager. The spacecrafts have travelled beyond where any human-made object has gone before, and were the first to photograph the planets up close.

Sloan Science & Film spoke in person with Irish director Emer Reynolds after the film’s Tribeca premiere.

Science & Film: Why did you want to make a film about the Voyager space missions?

Emer Reynolds: I have been madly in love with Voyager since I was a child. I never saw it as an American story; I thought it was amazing that we had the imagination to say, what’s out there? Could we get there? As a child I was blown away by the exotic. I would watch BBC’s show THE SKY AT NIGHT with Sir Patrick Moore, and he would do an item on Voyager every month.

S&F: Voyager is a universal story about humanity trying to communicate with aliens, but it is also a story about the American space program. How have people around the world been responding?

ER: It is a uniquely American success story. That is wonderful to celebrate. At screenings, there have been real outpourings of pride not only at American achievements in space but at their scientific prowess, their ambition, and their curiosity. It was a country, arguably it isn’t now, that embraced all of that and saw the value of asking questions. Scientific curiosity was prized in this culture.

We have showed it to European audiences as well; we premiered at the Dublin International Film Festival. What they hooked into is the human story. NASA and JPL talk about Voyager as being sent out not just by Americans but it was sent out on behalf of humanity. When we showed the film last night, one woman came up to me who was from Bulgaria and she was crying and saying, it had the Bulgarian chanting. She was very moved that her culture was represented. When the earth is long gone and humanity is a distant memory, her music and her culture will be out there.

S&F: The images in the film are amazing.

ER: We wanted to showcase Voyager’s images because they are extraordinary. Perhaps Galileo has taken further detail of Jupiter, and Cassini of Saturn, but these were the first. Voyager took big, high-resolution, gorgeous images. Much of what we know now, we know from Voyager.

S&F: Were NASA and JPL open to working with you?

ER: They were fantastic to us. We wanted to make a film that would appeal to a general audience, and they were on board with that. They are very into outreach and communication. We had thousands of hours of archive footage.

S&F: How did you cull them?

ER: One of the hardest challenges of the film was telling such a huge story with such a wealth of material in a feature-length film. Each planet could have taken up a feature-length film with the amount of detail, anecdotes, and great stories that came out. Like all films it seemed like a mountain you can’t climb and this journey of a thousand miles starts with a single step. Tony Cranstoun, our editor, is fantastic.

S&F: You haven’t made films before this having to do with scientific subject matter, so how was that? Were there any particular challenges?

ER: I have had a massive love of space since I was a child. I studied science in college. I read a stack of books for months before we shot trying to get my head around the concept. I wanted you to feel like you were clutching on to Voyager and along for the ride. Certainly the CGI images and the interviews with scientists do that. You feel invested in this little craft’s success.

S&F: Voyager 1 and 2 should have a Twitter.

ER: I think they do. They don’t tweet very much.

S&F: I’ve read a lot of scripts about the Golden Record, and I have interviewed the director Zach Dean who is now making a feature film about the love story of Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan working together to make the Golden Record. It made me wonder how you worked with Druyan?

ER: We tried very hard to interview her, for a long time, but for contractual reasons she was unable to take part, unfortunately. We were disappointed. We would have loved to interview her. We then had to focus on other people who contributed to the Golden Record such as Jon Lomberg, Frank Drake, and Timothy Ferris, as well as Nick Sagan, Carl’s son.

S&F: Had they all come together since Voyager?

ER: No, and sadly our interview period happened over two weeks so they didn’t meet. I asked them had they ever had a Golden Record reunion, and they haven’t. Perhaps they will.

S&F: Weren’t there some restrictions on what this team could include on the Record?

ER: They made a decision not to include images of war or poverty. They wanted to put the best foot forward. Frank Drake tells a great story: if you were taking photos of your family, you wouldn’t want to show everyone that Uncle Tom was a drunk. You censor it a little. I think their explanation was, you are communicating with an alien that knows nothing, and maybe images of war and nuclear bombs would feel like a threat. But, I think they should have come clean about what we are like as a species. If we went to record it again now, I think we should say how we are destroying the place.

S&F: We’re looking for a new home!

ER: Or, come and help us. Show us how you dealt with pollution on your planet. How did you deal with overpopulation?

S&F: I thought it was interesting what one of the scientists in the film said about how we have intelligent life even on earth that we can’t communicate with, such as whales and dolphins. It made me think of ARRIVAL, and how those aliens were like squids. It raised all these questions about how would we communicate? What would we say?

ER: We don’t even understand each other’s cultures. I wouldn’t be too optimistic about our ability not to shoot aliens down if they arrive bearing all sorts of technological advancements for us to clean up the air and the water.

S&F: At the same time, Carl Sagan made the good point that if there’s anything to make us realize our commonalities it is the view of ourselves from space.

ER: He was a poetic speaker, but he also had the scientific chops to say, this pale blue dot photograph has the capacity to cause a paradigm shift. When they were reluctant to take that photo he had the scientific clout to say, go ahead and make it happen. He is a massive hero of mine.

S&F: Why?

ER: In particular because of his poetic turns of phrase. In fact Nick, his son, has not fallen very far from the tree. He has the same use of language, and ability to connect on a deep emotional level.

THE FARTHEST will continue to show at festivals around the world. They hope to have it out in theaters by summer of 2017. It is written and directed by Emer Reynolds. Kate McCullough did the cinematography. It features Lawrence Krauss, Timothy Ferris, Frank Drake, Carolyn Porco, Nick Sagan, and Suzanne Dodd, among others. For more, listen to the Golden Record online, and read Science & Film’s interview with Zach Dean who is making a feature film called VOYAGERS.